| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Transcription of oral history for Subhash Chandra (141.88 KB) | 141.88 KB |

Description:

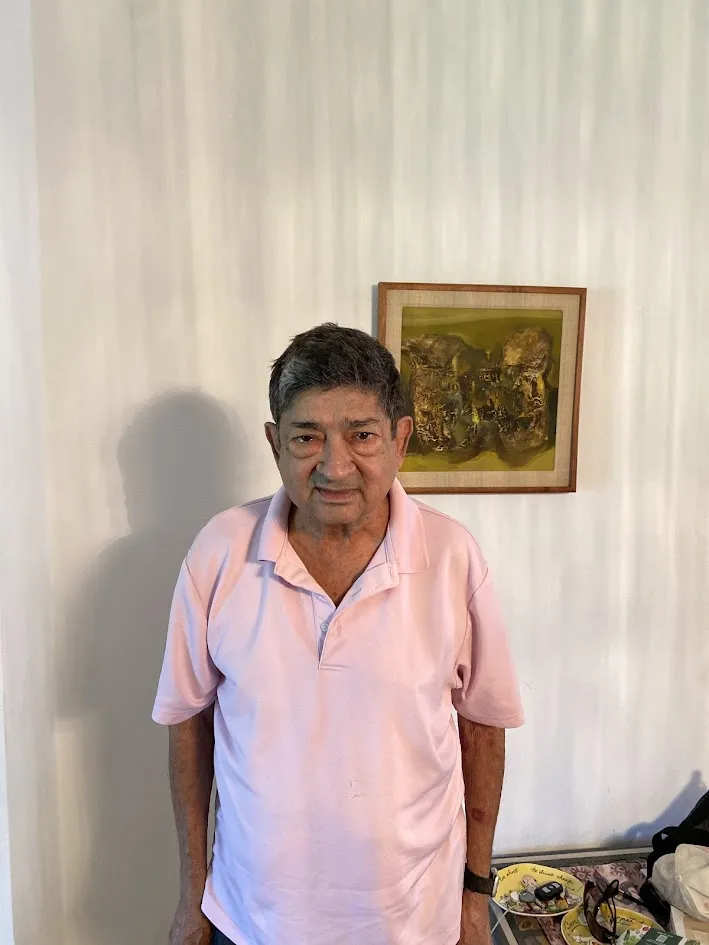

Subhash Chandra was born in Farrukhabad, Uttar Pradesh, India, in 1944. He recalled how India’s independence in 1947 affected his earlier years and his family more broadly. In addition to the challenges brought with independence, Subhash remembered the financial difficulties his family experienced during his childhood. A fascination with American society and culture, learned through films and word of mouth, and a desire to complete his higher education in the United States prompted him to leave India in 1968. Subhash discussed the similarities and differences between his pre-departure conceptions of the US and what he observed upon arrival at the University of Cincinnati. He specifically emphasized how the larger racial issues during the late 1960s and early 1970s and the Vietnam War conflicted with his idea of America standing as the “most advanced nation in the world.” As a result, Subhash connected with several Civil Rights leaders during this time. Conversely, however, Subhash recounted his amazement when seeing a professor lunching with a janitor, and how that never happened in India as a result of the rigid caste system. In 1974, Subhash graduated from the University of Cincinnati with a doctorate in engineering. In 1978, Subhash fulfilled his intentions of returning to India after completing higher education in the United States. Academic politics in India, however, soured his homecoming, and he returned to the US permanently in 1980. After decades of working with several companies in Connecticut as an R&D engineer, Subhash moved to Orlando, Florida, for his retirement in 2015. Through the Asian Cultural Association (ACA), Subhash connected with the Indian community in Orlando, serving as the organization’s president at one point. He outlined his motivations for serving in the ACA and the importance of its mission more broadly in Central Florida. Lastly, Subhash shared his observations about Florida, highlighting the state’s continuities and ruptures over the past decade, specifically underscoring political concerns and how pivotal the contemporary moment (c. 2025) will prove to be for Florida and American history.

Transcription:

00;00;04 - 00;00;23

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: This is Sebastian Garcia interviewing Subhash Chandra on May 15th, 2025, at Subhash’s home residence in Orlando, Florida for the Florida Historical Society Oral History Project. Can you please restate your name, date of birth and where you were born?

00;00;23 - 00;00;35

SUBHASH CHANDRA: My name is Subhash Chandra. My date of birth is 7-29-1944. And I was born in India.

00;00;35 - 00;00;36

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Where in India specifically?

00;00;37 - 00;00;45

SUBHASH CHANDRA: It was a small town called Farrukhabad in the province of UP [Uttar Pradesh].

00;00;45 - 00;00;47

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Is this northern India, southern?

00;00;47 - 00;00;55

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Yeah, it was kind of north and central India. And I was born before the Partition, before independence.

00;00;55 - 00;01;22

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Yes. And we will get to that. Well, actually, I will just ask you right now. You were around three years old when the Partition happened. So, I know you may not have vivid memories of it specifically, but can you just share with me sort of the atmosphere afterwards, or what your family told you about the transition between colonization [and] freedom?

00;01;22 - 00;03;16

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Yeah, we were really not directly affected by the Partition because most of the violence and misery took place at the border areas. Border towns. So we were not really affected by that. But I have some very vague, actually not so vague memories of one or two memories. At that time, my parents were living in this city called Haridwar on the northern part of UP and we were living in an apartment, and we were on the second floor and there was a balcony. So I remember, I am in the balcony, and I see a truck, people shouting, crowd of people shouting and yelling, and they got on two or three trucks and sped off. I had no idea where they were going. I was scared, and perhaps that is the reason I remember. I have that memory, but I remember that. And then there was an open plot of land next to an apartment, and, I remember some old man, he came to our house, and my mother gave him food, and he had a huge gash in his thigh. That upset me very much. I had never seen something like that. So I did not know the reason for that, of course, I was too young for that. But I do have some a couple of incidents that I remember.

00;03;16 - 00;03;34

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And can you recall broadly that period of transition for freedom once you were a little bit older, like still in your childhood, but how did the new independence affect your family and you?

00;03;34 - 00;07;19

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Then we moved to a place called Allahabad, and that was where I grew up. And maybe I think we moved there when I was four or five years old and, what I remember is that we had a lot of refugees, Hindu refugees from Pakistan who had left Pakistan and came to India, and they had no place to go. They had no relatives, no friends, no house, no money. They just literally left with the clothes on their backs. So the government was settling them. So they were given land in different cities all over the country. So these refugees had started moving into our city and our city was a very conservative city at that time. But these people changed the culture. And typically some people actually did not like the cultural change, we did as young people because they were Punjabis and they had their own food and their own cultural thing, music, which we as young people really enjoyed. And they were very hardworking people and within I think eight or nine years, they had become maybe the most prosperous community in our city.

And when I grew up, became a little older and started understanding the politics, the social things a little bit more—it was a time of transition for India. We had opted for democracy, parliamentary democracy, but it was not perfect. And I think there was a lot of resentment. And so big discussion that used to take place among the young people as well as the older people, is what kind of governance India needs. Is democracy the ideal or some kind of dictatorship is the ideal way to deal with India's problems or communism? In fact, two or three states in India did become communist, and stayed communist for a very long time. So there was a lot of discussion going on. There was also discussion on Hindu-Muslim issues. How do you deal with the Muslims and how do the Muslims deal with India? What was their role in India? What was that? How did that contribute to the society in India? So all those were topics of discussion. And, of course, in India caste is a big issue. And after the independence, the people in the lower caste who had been suppressed for centuries, they started speaking up. They started demanding their rights and so it was really a period of turmoil. A lot of things were happening at that time.

00;07;20 - 00;07;25

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And can you just tell me, what did your parents do for a living?

00;07;25 - 00;07;30

SUBHASH CHANDRA: My mother was a homemaker. My father worked for the government.

00;07;30 - 00;07;33

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What did he do in the government specifically?

00;07;33 - 00;07;49

SUBHASH CHANDRA: He worked in this alcohol abuse, educating people not to drink and stuff like that, of course, but he used to have his drink.

00;07;50 - 00;07;52

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: That was very interesting. Were you an only child?

00;07;52 - 00;07;58

SUBHASH CHANDRA: No, I am the youngest of three.

00;07;58 - 00;08;10

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Besides, sort of the broader political conditions, were there any other particular challenges that your family faced during this time?

00;08;10 - 00;09;20

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Money. We were not wealthy people, middle class to lower middle class. So, money was always an issue. Although, nobody believed that we were poor because back in those days, there were a lot of bungalows, huge bungalows built by the British. And they were up for rent. And in India, at least in our state, there was a rent control act, so if you managed to get those property, you literally paid nothing for them. So I grew up in a house that was like three times the size, four times the size of the house we are sitting in. We [rented] half of it, with lots of land and what have you. So people thought you we were wealthy people, but we were not.

00;09;20 - 00;09;27

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Is there any other notable memories you have about your childhood during this time?

00;09;27 - 00;11;26

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Yeah. The house I lived in was a very interesting house. I mean, it was an old house, the bungalow, huge rooms, high ceilings, barandas, outside barandas, inside barandas, beautiful house. And beautiful flower gardens in the front. And my mother used to have a huge vegetable garden on the side. And so my primary school took place—the classes were held in the morning. So I used to go to school at maybe seven, seven thirty, or something and then come home by noontime. So my afternoons were completely free. So after you did the homework, you had nothing to do. And my two brothers, they were older than me, and they went to the day school. So I was alone. So I grew up almost as an only child, and I used to walk around on the yard. And we had all kinds of fruit trees and a hundred guava trees and hundreds of mango trees and every fruit you can imagine, we had them. And so just walking around and just not doing nothing. And it was the most memorable thing I did as a child, I really enjoyed it. Just lie down somewhere and look at the clouds and all that sort of thing.

00;11;26 - 00;11;33

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: How was your schooling experience like in India?

00;11;33 - 00;11;55

SUBHASH CHANDRA: It was tough. It is a lot different now. But I was pretty smart, so I sailed through, never had any difficulties. Actually, I did pretty well. Well, my schooling included the college days.

00;11;55 - 00;11;58

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What did you study in college?

00;11;58 - 00;12;02

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Mechanical engineering.

00;12;02 - 00;12;04

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And where did you attend?

00;12;05 - 00;12;06

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Allahabad University.

00;12;06 - 00;12;08

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And where is that?

00;12;08 - 00;12;25

SUBHASH CHANDRA: In my city, Allahabad University. That was a very old city. I think one of the first four to five cities established by the British.

00;12;25 - 00;12;40

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: When—so what year—and what were the circumstances that led you to leave India and emigrate to the United States?

00;12;40 - 00;13;38

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Fascination. We used to watch Hollywood movies. And so you were fascinated by the country, by the society. We had heard stories about how good the life was in the US. I wanted to study, for the graduate studies. And there were very few graduate programs in engineering back in India in those days. So I think that was the main motivation for coming here. And again, as I told my mother, I would go to the US, I promised her, I would go to the US, get my PhD, work for a couple of years, save a little bit of money, and come back. And I am still here.

00;13;38 - 00;14;01

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: You just mentioned how you were fascinated by American society and culture through films. In what ways did your perceptions change once you did come to the US about American society and culture?

00;14;01 - 00;15;57

SUBHASH CHANDRA: In some ways it became more positive. In some ways it became negative, very negative, more positive because I saw back in Cincinnati in those days, the typical Midwestern kindness. They were gentle, good people, polite, respectful, caring. So I was really touched by that. Of course, they knew nothing about India, so I used to get my share of ridiculous questions, which was fine, that did not bother me. But what bothered me was the race issues. And then when I came here, Vietnam War was going on in full steam. Now, back in India, we hardly used to get any news of Vietnam War, once in a while, some story would show up in the newspaper. But nothing, nobody knew anything about the Vietnam War. And we did not consider communism to be as much of a danger as the Americans did. So when I came here and all of a sudden, people are talking about the Vietnam War and—what is that term when things fall in sequence. I forget, it will come to me. They were saying states are going to fall once South Vietnam is gone, the north will be gone, and then another country.

00;15;57 - 00;15;58

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: The Domino Effect.

00;15;58 - 00;19;31

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Domino effect. And I am saying, “Well, what domino effect are they talking about?” We had a province that was ruled by communists, and they were human beings just like us. So I used to wonder, “What are these people talking about? Why are they fighting?” And then the CBS news, Walter Cronkite, showing pictures of dead American soldiers or injured American soldiers and the kind that I found so objectionable [was] the body count. “150 American soldiers died. 500,000, North Vietnamese killed.” It was that ratio, “200 American died. We killed 15,000 North Vietnamese.” And the casualness with which they said as if these people were animals. So that used to bother me, I cannot consider anyone as an animal. And then the Civil Rights Movement was going on too, and I had the fortune of meeting two very smart Black people, highly educated, Harvard educated. One was a great artist. There is a museum named after him in Cincinnati, and much older than us, but they kind of took me under their wings. And so I used to go to their house, and we would talk about different things. And through them, I met some civil rights leaders and other people, and that bothered me. And again, coming from India, they were treating the lower caste people the same. And I objected to that. But I saw the same thing here, and I could not believe it because I used to think India is a backward country, so if something has happened, there is a reason for that. But America is the most advanced nation in the world. So how can they do this? How can they? So yeah the answer to your question—yeah, a couple things really were great. My professor, a big tall man, Ohio guy, and I could not believe it, we had a janitor in our building and, every day, this head of the Department of Aerospace Engineering and this janitor used to go for lunch together. And I am saying, “could I have done something like that in India?” No. So those were the good things.

00;19;32 - 00;20;04

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Yeah. That is fascinating. Thank you for sharing. And I am curious, since you were so aware and on some level involved with the Civil Rights Movement and Era, did your identity as an Indian man ever affect you? In other words, like I am looking at you your complexion is kind of like mine. Did you experience any racial thing like that or no?

00;20;04 - 00;20;43

SUBHASH CHANDRA: No, none. Not explicitly. No. I mean, people had trouble understanding my accent or taking my name, but other than that, there was no real bad experience. I mean, people were curious about us, you know, “Where did you come from? What did you do? And how are our things in India? Do you still ride elephants and live in the trees?” Yeah, those questions did come.

00;20;43 - 00;21;15

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: But nothing explicitly. Okay. And you left in ’68. So we have that for the record. You were sharing with me before we started recording how, Neil Armstrong, the astronaut, would come to your department in the University of Cincinnati. Just talk to me about that, that is very interesting.

00;21;15 - 00;23;40

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Yeah, it really came as a surprise. Of course, we watched the moon landing, and that was one of the most amazing things that I have seen. Then, one day there was an announcement in the newspaper that Neil Armstrong is joining University of Cincinnati as a professor. He had retired from NASA. And we used to live in a married student's dorm that was like eleven or twelve story building. And there were two penthouse apartments. And so the news came and the first day he came to the university, they were press reporters. Everyone was there, a lot of hoopla. And then he did come to the department a few days later. Our head of the department, his name was Tom Davis, and all the teaching assistants, graduate assistants, we used to sit in a bullpen somewhere in one of the rooms, we had a little cubicle, and so he brought Neil Armstrong. He took him around and introduced him to everyone. And I still remember he comes to my cubicle, and he says, “I am Neil Armstrong.” I said, “Are you kidding!?” The most famous man in the world. I mean, that was how humble he was. Amazing guy. And then it so happened in our dorm, one of the penthouse apartment was occupied by the dean of engineering, and Neil Armstrong lived on the other one. So we used to see him in the elevator all the time, and he would say hello to whoever was there, and it was good. But that was fascinating.

00;23;40 - 00;23;47

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: That is incredible. So when did you graduate from the University of Cincinnati with your doctorate?

00;23;47 - 00;23;52

SUBHASH CHANDRA: ’74. I got my degree in ’74.

00;23;52 - 00;23;57

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And you entered the workforce immediately?

00;23;57 - 00;23;5

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Before that. ’73.

00;23;59 - 00;24;04

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Talk to me about that transition in your life from school to now in the workforce.

00;24;04 - 00;26;37

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Oh, school, I was making $300 a month and we could not live in that. So my wife had to take a job. So she took a job in a medical lab. And she was making, I think, $400 a month or something. We were rich. We were very rich. And, in fact, I even bought a car. Ford Falcon, 1962 Ford Falcon, sky blue in color. Great car. So I bought that car. Then when I got the job, at Babcock and Wilcox, my salary was, I think, $18,000 a year, and we did not know how to spend that money. It was just way too much money for us. But I remember when we left Cincinnati and drove to Lynchburg, Virginia for my job, I had zero money with me. The company had moved all the stuff over, we did not have any furniture, but whatever we had in the apartment, they had moved, and they had put it in a storage because we did not have an apartment in Lynchburg. So we started looking for apartments, and the company had put us up in a motel. So when we started looking for an apartment, the rent was like $150 a month, but then, you had to put two months’ rent in advance. We did not have $300. So I went to my boss, and I said, “I do not have any money. Can I get some advance on my salary?” He said, “It does not happen that way.” So he said, “Go to the bank.” He knew the banker. He said, “Go to the bank and tell him that you are working for BMW, and they would give you a loan.” So I went there and talk to them. And within an hour we had $1,000 in our checking account, so we could rent the apartment, then no furniture, so we rented the furniture, it was—but it was a lot of fun.

00;26;37 - 00;26;50

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And you mentioned to me earlier how you promised your mom that you would go to the United States, get your degree, worked for a little bit, and then come back. Did that happen?

00;26;50 - 00;26;53

SUBHASH CHANDRA: No.

00;26;53 - 00;26;55

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So you never returned to Indiana?

00;26;56 - 00;27;56

SUBHASH CHANDRA: We actually did. At the back of our minds, we still wanted to go back to India. Settle down there. So it did not happen after five years, but we did go back in I think ‘80 or ’81, and I got a job to teach at a university in Delhi, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. And we took that job. We sold our house and moved back to India. But my son was having trouble, I ran into some political things, departmental politics, academic politics and, I said it was just not worth doing that. So we decided to come back.

00;27;56 - 00;28;14

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And, as I asked your wife earlier, do you think there was a stigma that you left India and you came back, like that second time that you were in India, sort of like you abandoned your home country, and now you are back like “how dare you?” Things along that line.

00;28;14 - 00;29;50

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Some people did. Some people did feel that way. You see, there was a gap and people thought that we owed it to that country—and they did gave us a free education. I got free education and pretty much a free ride. So we owe the country something, and we wanted to do something. But if you are not willing to take what I am giving, what do I do? So, yeah, some people say, “Oh, you should have stayed there and done this,” but we tried. We could not do anything. They would not take it. So we came back, and it was a difficult decision—difficult to leave this country and go back and then difficult to come back to this country. Both decisions were very emotional and difficult. But we actually enjoyed India a lot. Not the work part, but everything else was amazing. And we made some good friends, and we still are friends with them. We traveled. So we had a great time.

00;29;50 - 00;30;03

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: How was it like coming back? You just mentioned it was difficult, but you had been here before, so the transition was not too challenging. Just talk to me about that experience.

00;30;03 - 00;30;52

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Coming back? See, India is a very vibrant country. You know, there are people everywhere and noise and colors and everything. So, it is a very vibrant culture, people talking to you and all that. When I came back here, we were sitting alone in the apartment and turning the TV on and watching “Laverne & Shirley,” one of the most stupid shows ever. And I was like, “Is this why I came back? Leaving that life and coming back to Laverne & Shirley every night?” I was upset.

00;30;52 - 00;30;56

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And when you came back did you returned to Cincinnati or different state?

00;30;56 - 00;31;04

SUBHASH CHANDRA: No. I had started working for Combustion Engineering in Connecticut and they took me back.

00;31;05 - 00;31;14

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And how long did you work for that company?

00;31;14 - 00;31;31

SUBHASH CHANDRA: I think eight or nine years there. Then Northeast, for maybe twenty, twenty-two, state of Connecticut, four or five, and then back to Combustion for another eight or nine.

00;31;31 - 00;31;39

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Describe to me your job in all these different iterations. What did you do?

00;31;39 - 00;32;54

SUBHASH CHANDRA: For both Westinghouse, Combustion, Babcock and Wilcox, we were designing nuclear reactors. So I was doing mostly R&D [Research and Development] type, work and also writing papers and coming up with new methods for analyzing different structures. So I did that. When I worked for Northeast Utilities, it was more as a project manager. If there was a problem, if something broke, they would come to my group, and we would find a solution for it. And we had a very busy time. Five nuclear power plants. And, yeah, something was going wrong all the time. So, you are busy all the time. All year round. But interesting job. Very interesting. Technically, intellectually, very, very interesting job. And I really enjoyed it.

00;32;54 - 00;33;03

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And when did you move to Florida? Was this for retirement? Why did why did you come down here?

00;33;03 - 00;33;34

SUBHASH CHANDRA: My son was already here, and we had been thinking about leaving Connecticut. The weather was becoming too cold. And the last year we were there, before we made the decision to move finally, we had a blizzard that lasted two days and dumped about thirty inches of snow. I said, “That is it. We are going to Florida.” So we moved here.

00;33;34 - 00;33;36

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And what year was that?

00;33;36 - 00;34;03

SUBHASH CHANDRA: I forget. We started coming here around—looking for houses—2006 or 2007. And then I think we ended up buying a condo 2008. So she [Madhu Chandra, his wife] was retired already. So she was spending more time here. I was still working, so I used to come for a week at a time.

00;34;03 - 00;34;15

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And once you did settle here, how different was Florida from the northeast in your mind?

00;34;15 - 00;35;07

SUBHASH CHANDRA: I mean, the weather wise, it was obvious. But, culturally, just a totally different environment. Northeast Connecticut, highly educated, more liberal. Florida tends to be much more conservative. And the divide has become a hell of a lot wider now than it was when I moved here. So it was different. It was very different than Connecticut.

00;35;07 - 00;35;13

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: When did you become involved with the Asian Cultural Association [ACA]?

00;35;13 - 00;35;16

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Right around when we moved here.

00;35;16 - 00;35;18

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: How did you discover it?

00;35;18 - 00;35;58

SUBHASH CHANDRA: I think my wife, she was in music, and I think she somehow got in touch with Jasbir [Mehta], through music or some concert or something. And they hit it off. And I was looking for something to do. Retired. Nothing to do. I mean, I was playing golf. I started taking some courses at Rollins and then Jasbir said, “Why don’t you help us out?” So I said fine. So that was how I got involved.

00;35;58 - 00;36;04

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And how has your responsibilities changed since you have been involved?

00;36;04 - 00;36;08

SUBHASH CHANDRA: I am slowing down. Yeah. So I have been—

00;36;08 - 00;36;08

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: But initially what were you doing?

00;36;08 - 00;36;2

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Initially helping out, organizing things and helping her any way possible. But now I am slowing down, so I am more of a cheerleader than a real worker.

00;36;26 - 00;36;31

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: How did you become president of the organization?

00;36;31 - 00;36;47

SUBHASH CHANDRA: I think they were looking for somebody. And they probably wanted somebody older. And I had the interest, and I was a project manager, so I could organize things.

00;36;47 - 00;37;00

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And yes you needed something to do, but there is plenty of things to do in retirement, why was it important for you to be involved with an organization like the ACA?

00;37;00 - 00;38;29

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Oh, absolutely. Because this organization was serving or is serving a very important role for the Indian community here. Indian classical music is thriving in India, but it is dying here. And I think it was very important to revive it, keep it alive, and also to make other people, other communities become aware of the Indian classical music or classical arts, actually, not just music. So we used to have music conferences. We would run summer camps for children, arts, dance, music for children. So there were a lot of activities we were doing, which I thought were important for the Indian community and not just Indian community, others, too. I mean, we had programs that appealed to the Hispanic community, Spanish community. So it was a lot of things that needed to be done.

00;38;29 - 00;38;48

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: I am curious you have been here for ten plus years or more. From your perspective, culturally, how has Orlando changed since you have been here? If you think it has changed.

00;38;48 - 00;40;31

SUBHASH CHANDRA: I think it has changed. I think it has changed a lot. And I think culturally it has become much more tolerant of diversity. I mean, look at the arts scene in Orlando, which is really thriving. Music festivals and food and movies. I mean, ACA organizes this South Asian Film Festival, which has been going on for thirty, forty years or so, and we got some really interesting indie type films that attracts a large audience. So, I think the art scene has become and culturally I think, look at the food scene, when we moved here, the food scene, except for Park Avenue and Winter Park and maybe near Disney, but it was really dismal. There were no good places to eat and look at it now. We have how many Michelin ranked restaurants now and more are coming up? Colonial Avenue used to be a dump when we moved here. But look at it now. It is thriving. Restaurants are opening, shops are opening. So, yeah, I mean, I think things have changed. A lot of things have changed for better.

00;40;31 - 00;40;43

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What challenges does Orlando face today?

00;40;43 - 00;41;58

SUBHASH CHANDRA: That is a tough one. I think the cost of living increases, housing has become much more expensive. And insurance and automobile insurance, homeowner's insurance are just going through the roof. And that it is going to have an effect later on. And population in Orlando is growing because it is a very attractive place to come to, to migrate to. But if the cost of living and these thins keep going the way they are, I think people may not come here as often. And the other thing is just the national, the political divide between right and left, and conservatives and liberals, I mean, it has gotten really ugly. And Orlando is like a little blue island in the red sea.

00;41;58 - 00;42;19

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Yeah, absolutely. And relatedly, you mentioned before we started recording how it has been a big change since you have arrived here in the late 60s, early 70s. So this is a broad question. And I am asking because you mentioned it. What were you referring to that when you told me?

00;42;19 - 00;44;43

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Well, everything. When I came here, [we were] young. I did not know anything about the country. And, I mean, just physically the physical appearance of the country, all you saw was—well, first of all, houses looked different. The cars were very different. The shops were very different. The there were not too many Indians at that time, so there were no Indian grocery stores. So we had no Indian food available in Cincinnati. So things were different. But…I lost my train of thought. I think the country has changed. Yeah. So that was what I was saying—all you saw was white folks everywhere. And what now you see is the browning of America. The first time I went to California for a business meeting back in the even early 80s, forget about 60s, I mean, people used to talk about blue eyed blonds of California, right? Remember that? You go there and now, I mean, majority of the people are, brown folks. Even Orlando has become the white minority community. So I think that has been a big change. Asians and South Americans, other people, and they are doing very well. They are contributing to the society. They are working. They are leading a good, honest life. But I think that has created a little bit of a concern among the rest of the folks. But that has been a change. Big change.

00;44;43 - 00;44;52

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: From your perspective, how will Orlando change in the next twenty five years? How do you think Orlando will change the next twenty five years?

00;44;52 - 00;45;56

SUBHASH CHANDRA: I think the direction in which this country is going, I think we are at a very crucial moment right now. It can either go this way or that way. There is going to be a clear—it is not going to be any muddling through—it is going to be either this or that. And that is a very nationalistic approach that the Republican Party and the [Donald] Trump people are promoting, or a more multi-cultural, more diverse, society that the Democrats are proposing. And I think we are going to decide within the next few years which way we are going to go. So we are, I think, at a very pivotal point, in the history of not just Orlando, the whole country.

00;45;56 - 00;46;14

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Absolutely. How has your Indian heritage influenced your perspective on life generally, but also living in the United States specifically?

00;46;14 - 00;48;52

SUBHASH CHANDRA: My Indianness. I mean, I am not a religious person, but the Indian culture or even the Hindu. I am a Hindu. Even the Hindu culture. And it is not even just Hindu, it is a combination of Hindu, Buddhist way of looking at things. For example, we are taught, and I believe, and as you get older you become wiser. You know what matters and what does not matter. You also know that everything is—the impermanence of the society, that nothing is permanent. So you have to let things go, do not just hang on to things. So that is the Indianness I have. And to a certain extent, and I remember reading, I used to read a lot, and the books I read, the philosophical books, more philosophical books. Fiction, nonfiction. They also say the not quite the same thing, but very similar so it is like a universal truth, regardless of religion or culture or something. You know, you eventually come to that point, come to that type of thinking. So I do not think, I mean, it is not like there is a division. I mean, it is a combination of everything. And the life lesson is the, you are going to go, you are going to die, you are going to lose things. You win some, you lose some in life and accept what you have. Be thankful for what you have, and do not worry about what you do not have. And be kind to people. Be nice to people. Do not hurt anyone. All human beings are created equal. The fundamental truths. And they become more ingrained now than they ever were.

00;48;52 - 00;49;05

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Lastly, if someone is listening to this recording fifty or a hundred years from now, what do you want them to know about your culture and the state of Florida?

00;49;05 - 00;50;09

SUBHASH CHANDRA: It is a great state. It is beautiful. Florida is a very beautiful state. You know, beaches and rivers and lakes and just a very peaceful, very nice place to live. Fifty years from now, what will they think of us? Or what do I want them to think of us? Yeah, it is a good state. It is a good city that we are living in. But we are going through a tough time—not a tough time—but a crucial time in our history. And let's see how we behave. I do not know how we are going to behave.

00;50;09 - 00;50;25

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Actually, this is the last question, because I remember you told me this before we recorded, if and I am using it loosely because you might, if you were to write a memoir, what would you title it and why?

00;50;25 - 00;51;05

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Oh, that is a given: “From Bullock car to Concorde” Before the interview started, I told you, I remember vaguely going in a bullock cart with my parents in a village, and then I had the opportunity to fly in Concorde from London to New York, at twice the speed of sound, at 65 or 70,000ft altitude. What an amazing experience it was for an aerospace engineer. So. Yeah. And I have come a long way.

00;51;05 - 00;51;12

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Absolutely. Subhash, thank you so much for taking some time out of your day to share your life story with me. I really appreciate it.

00;51;12 - 00;51;13

SUBHASH CHANDRA: Thank you.