| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Transcription of oral history for Kymbat Iglikova (190.09 KB) | 190.09 KB |

Description:

Kymbat Iglikova was born in Talshik, Kazakhstan, in 1984. She recounted memories of her upbringing, particularly the uncertainty that followed Kazakhstan’s independence after the fall of the Soviet Union, as well as fond recollections of her parents and grandparents. Kymbat wished to pursue a career in chemistry; however, her mother discouraged her from working in such a field, citing geographical and gender concerns. Instead, her mother suggested that Kymbat pursue a career teaching English, recognizing the potential with increased globalization and companies investing in foreign areas, such as Kazakhstan. Kymbat followed her mother’s advice and graduated with a bachelor's degree in education, foreign languages, literature, and linguistics from Kokshetau State University. Ironically, this career path led to what her mother partly feared—moving away from home. In 2005, Kymbat participated in a student-teachers exchange program that provided opportunities to practice linguistics and teaching skills in another country, resulting in her departure from Kazakhstan and subsequent emigration to the United States. She spent two weeks in New York City, recounting a specific emotional memory that Kymbat credited as the reason why she ultimately stayed in the US. Kymbat requested that her agency transfer her to Florida, as she felt restricted in New York and wanted to reconnect with friends living in the Sunshine State, thereby rekindling her ties to Kazakhstan. Upon arriving in Florida, Kymbat founded Multilingual International Services and explained in extensive detail her inspirations to create the company, its purpose, its evolution, and how it intertwined with her other career in real estate. In 2019, Kymbat joined Orlando Fusion Fest, supporting their mission and expanding their programming to include Kazakhstan cultural showcases. Kymbat discussed what she has learned about Florida from her various professional experiences, including her linguistic company, real estate business, and Fusion Fest service. Additionally, given her intimate contact with recently arrived immigrants, Kymbat expounded on the current state of immigration in America (c. 2025) and how it differs from her personal experience twenty years ago. Lastly, she shared her broader observations about Central Florida, its cultural continuities, changes, and challenges since 2005.

Transcription:

00;00;00 - 00;00;18

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: This is Sebastian Garcia interviewing Kymbat Iglikova on May 26th, 2025, in Orlando, Florida, for the Florida Historical Society Oral History Project. Can you please restate your name, date of birth and where you were born?

00;00;18 - 00;00;28

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yes. My name is Kymbat Iglikova. I was born on June 1st, 1984, in northern Kazakhstan.

00;00;28 - 00;00;30

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Where exactly in Kazakhstan?

00;00;30 - 00;00;48

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: There was a little town called Talshik, which is about a couple of hundred kilometers from the Russian border, somewhat bordering Siberia.

00;00;48 - 00;01;06

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Can you tell me about your childhood growing up in Kazakhstan during the 90s and especially if—you might have been young enough to remember sort of the transition from the Soviet Union to the post-Soviet Union world. Can you just talk to me about that?

00;01;06 - 00;06;29

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yeah, absolutely. I think it was an interesting time. And I think I call myself lucky because I was born in the time where it was still the Soviet Union. But then I grew up as more of an adult child, when the country became independent and the fall of the Soviet Union. I would probably say, looking back now as an adult, it must have been a very challenging time for our parents because everything felt, people were questioning as whether they lived for the last seventy years, was that right? So people were fighting whether the Soviet rule was right, whether their new independence, where are we going? It was a time of a crossroads, but also an era for the country to start its own journey, its own history independently and to be able to revive our cultural heritage, to be able to speak our native language without second guessing ourselves and to really become an independent country and start its own journey and course. And I think that, at the time as kids, now that I look back, to me, it was the happiest time. We did not have much. I did not have computer growing up. I did not have any of these games that kids now use, Nintendo or any of that, Super Mario.

I grew up in a small town, but there was something there, something beautiful. We lived a simple life. Our neighbors and our town, we were all somewhat in some way, shape or form related to each other, but there was this closeness. So if someone did not have money per se for something, then you always knew you could go to someone to borrow that, right? There was no credit cards. There was no such thing as debit cards. Credit cards. And there was none of that. But I think that I look back, I was the happiest. I was the happiest. We played outside. I rode bicycles with my friends. My favorite thing was, and I guess early on was like a person who would rally everyone to do picnics to create little show for our parents for like, different holidays, we would dance, and I would be like the instigator of all of that. I think that my dad used to always say that “Oh my God, there we go a picnic again summertime.” I think it was the it was the happiest time.

One of my earliest memories as a kid, I was maybe four or five, I remember being summer time—somehow to me, summer was a happy time, maybe that was why I moved to Florida—and my grandfather was still alive. And the two of us, drinking, having breakfast, having morning tea. And I am running to tell my mom and dad to get up and have a tea with us. But of course, those two have a long week of work, and they just wanted to have an extra sleep, and they would not get up. So I just remembering that time and I would try to wake them up. I think that was the time. Another happy memory is with my grandmother. With my grandmother and grandfather on my mom's side, maternal side. And I would also spend a lot of time with them, especially my grandmother, because I think I was one of the few older grandkids and I feel closeness and then she would teach me a lot of things. She would tell me a lot of things. Her food. Now, back then, when I was a kid, I think about it, I was a little bit brat because I would say “Oh, is that the same thing we eating today?” Now, I wish I would have her real yogurt, by the milk that she milked that morning, and her fresh cream that she made herself using that old fashioned by hand thing and fresh bread that she baked herself. And then sometimes in the summer, it will be the chicken wherever she [grew]. And sometimes my grandfather would go in the morning and catch a fish, and she would just fry potatoes, like the country style fried potatoes, fried fish, yogurt, bread, I mean, that was just simple food. And how dare did I say to my grandmother “this again?” Now I would give everything to have that meal again with them.

00;06;29 - 00;06;31

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Were you an only child?

00;06;31 - 00;06;54

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: No, I have a brother. I have a younger brother. We are five years apart. He is a fancy prosecutor. He works for the Attorneys General Office back in my country, in the capital. So we are similar, but different.

00;06;54 - 00;06;57

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What did your parents do for a living in Kazakhstan?

00;06;57 - 00;07;34

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: So my father was an engineer by his profession. He worked for many years during the Soviet time as an engineer. But then when the Soviet rule fell, he was transferred because he was in the army before he was transferred into what is probably similar to the department of the DMV and the state troopers together. He worked in that department for the latter part of his year. And my mom was a CPA [Certified Public Accountant] for forty plus years.

00;07;34 - 00;07;35

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What is a CPA?

00;07;35 - 00;07;45

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: CPA, the accountant. So she still is. I mean, she is retired, but she still consults small companies.

00;07;45 - 00;08;05

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: You mentioned how growing up you did not have much like, much in terms of games and computers and material things. Besides that, were there any other particular challenges that your family faced during this time in the 90s post-Soviet Union independence?

00;08;05 - 00;09;40

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yeah. There was a time where people did not get paid for six to eight months in a row. Now, imagine you working six months and you are not getting paid yet. I think that sometimes when I talk to some of my friends that have immigrated from different parts of the former USSR, and I listened to their stories, I think that we were fortunate because we lived in a small town. We had our own livestock, we had our own cows, sheep, horses and so we were able to self-provide ourselves with food and sometimes we were able to sell some of the livestock in exchange [for] money. So I think that the main necessities, we did not have that need. The most important thing was the food so we would nourish ourselves. There were challenges that I felt that it was harder for my parents because they had to buy us clothing. They had to take care of us. Now that I look back, I do not think that I knew what were the challenges that they faced, at least I [never] realized, because they did a such a good job that we never felt that we were going through challenges.

00;09;40 - 00;09;44

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Were your parents also born in Kazakhstan and your grandparents as well?

00;09;44 - 00;09;53

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yes, yes. We were all born in the same town. I am like the third or fourth generation. I was born in a house that was built by my grandfather.

00;09;54 - 00;09;57

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Oh, wow. Do you know what year he built it?

00;09;57 - 00;10;05

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: I think he built it in the I almost want to say in the 40s of the 50s.

00;10;05 - 00;10;14

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Talk to me about your schooling experience in Kazakhstan.

00;10;14 - 00;11;35

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Amazing. It was not always easy because and again, kudos to my teachers. I would not say they were the best teachers of the world, but now that I compare, it was a small town. But amazing teachers. They were educated during the Soviet time. And one thing that I have to give credit to [is] the level and the quality of the education, during the Soviet time was very, very, very high, especially when it comes to science, like math, physics. I was in a what they call a physics and math class. So they separate the kids that have a little bit more advanced skills. So I was in that class with students that were doing much better or a little bit better than the others. So I think that pushed me to try harder. I never thought that I would be studying languages. My first initial thought was studying either anything pertaining law or anything pertaining like chemistry.

00;11;35 - 00;11;36

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So what happened?

00;11;36 - 00;16;16

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: So in the last two years of my high school, it was funny because we were driving, it was me, my late uncle, my mom. We were driving somewhere. And then my uncle was asking me, “So what do you want to do?” I said, “Well, I do not know. I am thinking it either I am going to go to law school, or I am going to do something with chemistry, anything pertaining the industry, maybe oil and gas,” because that was big in my country. So funny enough, my mom said, “Well, first of all, oil and gas. It was a big money industry, not a place for a girl. I do not want you to travel across the country.” It was in the west of our country, not a safe place, she said. I do not want you to be a prosecutor or attorney. Also not a great place for a woman at the time, slightly different times. And she said, “Why don’t you study languages? You can always you can graduate; you can always work as a tutor. You can always work as a teacher, as a tutor, you can work for a foreign company. English was becoming a thing at the turn of the centuries. A lot of foreign companies were coming in from Germany, from UK, from the United States.” So my mom saw it as an opportunity, but the level of English that I had in my school, that was the one subject in our school that was very poor quality because all of those English speaking teachers, they all left small town. They want to be in a big city. They want to be where the opportunities, where they can make money, not teach the kids. They could make more money by working for some foreign company like John Deere. We had a John Deere company that had an office in the northern Kazakhstan. Why? Because that was where we grow bread, that was where we grow wheat and obviously they wanted to sell their products. And who do they need to speak? To local business people or local authorities or local organizations. Right. They need someone who speaks English. So that was where most of the teachers were. So my English was like, I was graduating, I could probably barely say in the tenth grade, “what is my name? My name is Kymbat. The weather is beautiful.” And then maybe a couple more sentences. That was it. So in the last two years, my mom hired a tutor. And then, I went into university.

When I went into university, my level of English and proficiency was much lower than those students who, over the last ten, especially from big cities over the last ten years, that was their goal. They were like literally programmed to—English was their thing. But I was able to catch up with them in the first year. I am proud of myself because I was able to catch up with them in the first year. And when I was graduating, I was graduating a much higher level than many of the students that came in from some of these gymnasiums or special education. Some of them were taking classes at a college level. So, that was how I came about to the English language. And from then on, while studying there, there was a program, it was called a camp counselors student exchange and teachers exchange. So, because being the graduate student [at] the university, I had a Bachelor of education, this was a university for teachers, learning English, English and German philology. And so the opportunity was to go to another country and to practice your language skills and also your skills as a teacher. Because when you go to work as a camp counselor, you are working with kids. So that was where it all kind of started.

00;16;16 - 00;16;20

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So, what university was this? The name.

00;16;20 - 00;16;28

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: The name of the university [was] the Kokshetau State University. It was located in northern Kazakhstan.

00;16;28 - 00;16;49

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And was that always the end goal when you started in this career path to go to other countries? Because you mentioned how your mom really saw it as an opportunity to practice English, but in Kazakhstan. Right. Like when foreign companies came in, not you going out.

00;16;49 - 00;18;37

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: No, it was never a goal. I mean, think about this. Whenever my mom tells me or reminds me how many years I have been far away from them, I always say to her, “remember, you were afraid to send me to the West in Kazakhstan, and then you send me to study languages, right? And I end up even further away than western Kazakhstan.” So I think there are some things that are beyond our understanding. I think it is a destiny. You know, because I could have said no. When she was telling me in front of my uncle, “No, I do not want you to do this. No, I think it will be better for you to this.” And it was not that I am saying that, well my mom is being selfish, I do not think that way. I think she was trying to safeguard me from things as an adult that I would safeguard my daughter now. And the funny thing that happen is that my uncle reminiscent of the thing where my mom was going to university, she wanted to go to law school. I did not know that she wanted to go to law school. That means she would have studied somewhere, either Moscow, Saint Petersburg, somewhere in Russia, because that was where they had one of the best universities during the Soviet time. And apparently my maternal grandfather that time, which was her father told him, “No. I cannot send you there, not for girl. How about you become an accountant or CPA?” Because people would always need the doctors, the accountants and teachers. So it was kind of like—.

00;18;37 - 00;18;38

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: She passed it down to you.

00;18;38 - 00;18;44

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: She did the same thing. She sort of did the same thing, you know.

00;18;44 - 00;18;46

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So you never envisioned leaving Kazakhstan?

00;18;46 - 00;19;13

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: No, I do not think I ever did. Not for a second, because I have never traveled anywhere outside of my town. I think maybe another town further down. I have never traveled anywhere outside of my let's say maybe five hundred kilometers. I have never been on a plane. The first time that I have been on a plane is when I was on the way here.

00;19;13 - 00;19;16

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And what year was this?

00;19;16 - 00;19;18

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: This was 2005.

00;19;18;12 - 00;19;25;18

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And when you emigrated to the United States, where was it specifically?

00;19;25 - 00;20;42

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: My first port of entry was JFK, New York. I was supposed to go for several days to a week to Columbia University. That was where they were preparing us for the program. So that was my first place. Certainly it was exciting to be there in a place, at a university where such amazing people graduated or went to school. So that was very exciting moment to be able to see the Statue of Liberty, to be able to walk near the Rockefeller Plaza, where I have seen it only in the Home Alone [film], when he goes in to see the Rockefeller Christmas tree. It was just surreal. But funny thing that happened to probably several of us because I was not the only one, is that when we went down to eat breakfast in the morning, I could not eat the food. It was just to me I felt like everything looked beautiful, but it taste weird. It taste different. Something was missing. It took me a long time to get used to the food.

00;20;42 - 00;20;58

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Besides the food, once you settled here more permanently, did any of your perceptions about the US, if you had any before you came here, changed?

00;20;58 - 00;24;18

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: I think that what I liked the most, and I also think that maybe it is just who you are sometimes and the energy you carry and the kind of person you are, because I think everyone’s experience differently. I do not think I have ever had any unpleasant experience, ever. I mean, in a sense, when I first came in, I did not see any anyone who is not a foreigner but an American living here, that was not trying to help me genuinely, that was not trying to help me or trying to guide me a certain directions. And I also think that many people appreciated my hard work, honesty, politeness, and willingness to grow myself. And the fact that I spoke English very well to them. It always amazed them that how come your English is so much better, and you only here less than a few months? And that also gave me a leg up in being able to explain myself and understand the other person. So nothing was lost in translation with the exception of maybe one little incident, which I forgotten because this was a long time ago.

But one of the first time I went to a coffee shop. And I was just by myself. This was my first week and I just wanted to go out and try something order something, try it. And I did not realize it was a rush hour. It was early morning. Everyone is rushing to go to work, and I am not used to when someone is telling you quickly and the way that person spoke, maybe she was from a different part of the of the United States with a different accent, and I just could not catch up. I was like this, and I felt like she was telling me, hurry up, move. And I just could not, I felt like for a moment that I just grab something, then I drop something, and I was like, I walked out, and I started crying because I felt that something is wrong, that I could not understand her. And then there was an elderly couple, husband and wife that came out in American and they told me, “We are so sorry. She should have not done it for you. We are so sorry you did. You did nothing wrong. You did nothing wrong.” They gave me a hug, strangers. Complete strangers. And I think that made me realize that I am safe. That I am safe. Until something I watched recently, it triggered that memory. I think that if it was not for that couple who came out, who said you are safe, that you are in a safe place, you belong here kind of in their own way, I do not think that I would have stayed.

00;24;18 - 00;24;20

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Interesting.

00;24;20 - 00;25;02

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Something happened. You know, it is like this little trigger, right? And then other people that came along and I also think that, whenever I go, this is something that my grandparents taught me. Whenever you go, you remember, you are not alone. Your ancestors, their spirit, their prayers, their blessings are always with you. So no matter what people say, no matter what people do, no one can take that away from you. So I think that too, it was a combination of things. Maybe I saw my grandparents in them, maybe I looked at them and I thought these were my grandparents hugging me.

00;25;02 - 00;25;05

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: How long did you stay in New York?

00;25;05 - 00;25;09

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: We stayed maybe for about a week or two at most.

00;25;09 - 00;25;10

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Oh.

00;25;10 - 00;26;12

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yeah, for a couple of weeks. And then we were sent to a camp, and I cannot think of a name because it has been twenty years ago, but it was somewhere outside of New York. It was a summer camp. We were there for like about a month. And then I requested to change and come to Florida because half of the group was doing camp counselors. And then the other group was just doing summer work and travel on their own. It felt like we were a little bit too, how to say it was not much freedom. In our work there was no ability to travel except for maybe certain days. So I asked for permission to switch, and then to travel to Florida because I had some friends that were here, and they were just working and traveling. And I also felt like I wanted to be here to spend time with them and then to be able to travel and to see other places. And little did I know.

00;26;12 - 00;26;14

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: This was still in 2005.

00;26;14 - 00;26;15

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yeah, this was the same summer.

00;26;15 - 00;26;23

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So, and what else, if anything, attracted you about Florida besides your friends living here, or was it just that?

00;26;23 - 00;27;07

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Initially, it was just that because I want to be—you have to understand our culture, we are clam based society. So what does it mean, clam based society, that we have to be together with our little clan, whatever that is. And I just wanted to spend time with my—I felt like they were having a good time together, doing things together. I want to be part of that, if you will. And remember, I was still young. I was still a child that I have never traveled outside of United States, never traveled too far from my parents and family members. So that felt like going and visiting your family, if you will.

00;27;07 - 00;27;26

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Yeah. You currently are in the real estate business, which is, at least from an outsider's perspective, seems very distant from languages and English. I know you have a language company, and we are going to get to that, but how did you come to this real estate business in Florida?

00;27;26 - 00;27;28

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Well, it is interesting because it is connected.

00;27;28 - 00;27;30

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Okay. Then explain.

00;27;30 - 00;36;25

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yes. So, for over fifteen years, I owned my translation agency. I am an interpreter for over for as long as I have been here in Florida. Initially it was an immigration attorney whom I came with some of the other people from Kazakhstan to help them explain or translate. They actually hired me. And so that it gave me the opportunity and also opened the door. So initially I was able to start my own business as a translation agency. And I employ different languages, different people, not just Russian, Kazakh and English, we do all the languages. But, over the last twenty years, that ability to help people, whether it was for immigration purposes, whether it is their documents that needed to be translated when they are transferring this transcript, their education here, whether it is business delegation that was coming here from another country, sometimes it is a translation services for another country virtually. But it kind of kept me in loop with the community and community not just from Kazakhstan, but from former Soviet countries, the Russian speaking countries. Because that was the primary target language that I translate from and to. And why did one interpreting work led to the real estate was because more than one of the times some of those documents, lengthy fifteen, twenty page, business or other asset documents, was for real estate agencies. That was also some of my clients. And, as I was sitting at night translating this twenty page document, my husband said, “Well, why did not you do that? You helping these people, you translating for them, they working with someone, you doing a lot of work. This young lady is getting all this. But you maybe could be doing that.” And I thought to myself, that was very interesting. I took a course. It felt like it was somewhat interesting in the beginning. I did not plan to completely switch to the field and as I was going into that journey, I did not realize how many doors it opened to me. I was able to connect with the Asian Chamber of Commerce. I was able to connect with some of the other nonprofit organization to learn more about, what are the things some of these organizations do for the community? How do they help? I was able to help other people in businesses. I was able to help people that come from different parts of the world to invest into real estate. Some of them were students coming to study here, and their parents wanted a safe place for them to leave. Opportunity to invest, not just to pay rent. So it all came together as a full circle. So much so that it gave me the opportunity and opened the door into the leadership. So I have sat on a different associations. Currently, I am one of the board of directors of the state of Florida Realtors. We represent over 240,000 members. So this is the largest association in the country. Some even joke in the US saying that in Florida, someone may not have a driver's license, but they certainly do have a real estate license. So that was like a going joke. And there is a certain type of preconceived notion about individuals, realtors or real estate professionals. But I think there also a lot of amazing people like myself, that really go out of their way to help other people.

Like, I had a single mother from Kazakhstan with two children. Her husband passed away, and she was just left alone with two kids here in the United States. And I was able to help her find programs to where they will give her assistance for down payment. And she was able to buy herself a townhome. And I have a family like that from, Mexican American families, they are the first generation. She was the first one in her family who was able to buy a house in this country. And then her sister came shortly like a six or seven months later. She was the second one. Then it was their niece. And inadvertently, I became their kind of like, they call me a prima, which means cousin. Yes. But I also realized that we may be different culturally, right? Completely different parts of the world, but we have the same values and same values in a sense [that] we take care of our family members. We help each other. We want to be close to each other in. I felt like in some way, shape or form, they were closer to me in some way than maybe even some of the people from my country. I do not know how to explain it. It was just the amount of love that I received from the people, and I do not think I did anything extraordinary, but for them, I fought for them because they have tried to do that five years before that, and someone sadly did a shameful job, gave them the wrong information. They could not close. So I think that it was not without the challenges, but I think being an immigrant taught me, or being from another part of the world, going through challenges taught me not to give up. And that is how I approach when I take any case that, “let's turn it the other way around. Let's do it. Let's try this way we can turn it around.” It is like a LEGO right? “Okay, we cannot go this way. But maybe we will try this way. We should not go this way because that was what we going to face.” And I think it was, I do not know how to explain it.

I feel like in the beginning, I did not take it seriously. But then I realized I am helping someone, not just to buy house, but this is a home where they raise their family, where their memories are built. It is a lot more than that and sometimes we worked like, six to eight months to help someone get to their final destination. And every time they close, I close right with them. And I am also very proud that was in a group of the people with leaders of the Florida Realtors Association on the board where we fought really hard to give what is known as a down payment assistance for the heroes. They were a group of leaders that went to Tallahassee and fought for that program that now gives every person who lives in Florida, who works for the Florida company, and if they buying the home for the first time, they are qualified for up to 5% down payment assistance program, as long as they live in that house, they will never have to repay. They are not selling, if they lived in that home. So I think it is great when someone close in a home and they do not have to bring anything and they able to do that. And it is those things that makes me feel proud of what I do. It gives me energy. And fast forward to now, I think three or four years, not only I am able to help someone to purchase, but I am also teaching a new generation of realtors. I am now an instructor of real estate, so I help people to get the education through to be able to become licensed brokers or agents.

00;36;25 - 00;36;29

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Can you name the company of your translation service?

00;36;29 - 00;36;33

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yes. It is Multilingual International Services.

00;36;33 - 00;36;45

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And you have been doing it for twenty years, since 2005, two decades. In what ways has it changed, the company?

00;36;45 - 00;37;12

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: It opened the doors to other as—it kind of went hand in hand with my real estate business because it opened opportunities to other areas and industries, where initially it was mostly working with immigrants that are coming from different parts.

00;37;12 - 00;37;20

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: You mentioned challenges, while doing this translation service. What challenges did you face?

00;37;20 - 00;38;51

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Well, that is because Russian is not as popular as Portuguese or Spanish or maybe French or Creole. At least when I started, it was not as much request or as much of a business as it is now since 2020, since the COVID, there was a large influx of immigrants coming to United States from Kazakhstan from Russia maybe escaping whatever the situation is, Ukrainian population, escaping what is happening in that part of the world. So that population grew and many of them coming here, they do need the services. They need someone, as in the case, as we were speaking, someone just came to pick up their document. They are desperately need for their immigration interview, I think the day after tomorrow or tomorrow. And she is asking me, “Are you able to come? Auntie, please, are you able to come and help us? Apparently we need a life interpreter.” I am like, “I wish I could. I cannot because I have a class tomorrow. But do not worry, I am going to try to find someone who will be able to. I am going to try to get you someone who can come and help you.” So that is just how it is. But that was not the case in 2005, six, seven and eight. Those numbers were much smaller.

00;38;51 - 00;39;13

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And speaking of time I am curious, immigration in 2025 is a very contested topic issue. How have you navigated immigration through your company, especially since you are so connected with that community? And of course, as an immigrant yourself.

00;39;13 - 00;45;48

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: So I think that when I immigrated [twenty] years ago, I do not think that it was ever an easy process. It was never an easy process. And I think it is the same for many countries around the world. Like, if I were to just pick up and immigrate to Europe, I have to go through a certain due process. I always take it as my job to tell anyone who comes here and they happen to come to me to translate certain documents, and they ask me some questions, I always say, get an attorney, get legal advice. I am not an attorney. Let me get you someone. Get a legal advice, knowing what you want to do, or even if someone is coming to me and they wanted to purchase a home or invest what they have, for example, their children, the students they are studying here, and they want to buy a home or an apartment for them or condo. And they asked me, and I always tell them, “is there any chance that somewhere in the foreseeable future, you want your child to stay here, maybe immigrate here? Are you planning? Is there that thought? Because if that was the thought, then let's talk in with an immigration attorney and let's see what is that course of action. How do you have to take it? So you are never in a position to worry you overstayed your visa undocumented or you were violated certain rules.” So that is it important to me.

Now with that being said, other people that coming to United States that they have been coming for the last century to United States. Do they always come legally? Maybe not, but I always say, what is the reason that they come here? Do they come here because the life in their country so beautiful and they just leaving their home? Would anyone in their right mind ever be so desperate to leave their home to come to another place if it was not for whatever the challenges that they going through? I think that is very important to sense. And not everyone who is coming is a criminal. There are people like us, teachers, doctors, humble people from small town, maybe looking for a better future, maybe escaping war, maybe escaping some political regime in their country for the sake of their children. So their kids have a better future in a place that is safer, that have opportunity, opportunities for growth, for better education, right? For better life, quality of life.

What I think is happening, what was the difference between when I came here and what is happening right now? I think that people are having misconception. I think, there is a sort of knee jerk reaction. I almost want to tell some of these people with, very, how to say it, let's just say it is in a way dividing the country. And that is not healthy for any country. It does not create stability. It creates a division. And, it is not just healthy, not just for business, economic, political reasons. There are so many other reasons. If you look through any history of any country, if you look through this, this will come as with certain outcomes. We may not see it now, but years later, you will. What I also want to remind everyone, and no matter where they see it, if someone was to listen this twenty or thirty years from now, I want to remind all of them that this was a country that was built by immigrants. And when someone challenges me on that question is that what is the difference between me and someone great-great-great grandfather is a few hundred years. What is a difference between the two of us is that many, many moons ago, there was no immigration border, there was no immigration rules. And maybe those people also came, and they broke certain rules. But they came here for better future. They came here. They build bridges, right? They build railroads. Asian American. Right. Italian Americans, they built beautiful schools. They brought their beautiful culture, their restaurants and cuisine. And I think that no matter where you go in the world, you can never be that. Like you, Sebastian, come to Kazakhstan, you cannot be a Kazakh. You will still be Sebastian, an American of Latin American descent. Right. And when you come to America, no matter where you come from, you can become an American. And that is one thing that separated this country and for many countries around the world, that was something uniquely American, that American Dream people that come here, they want to be part of this. They want to live this life. Even let's say we talk about some countries that maybe do not like us, but deep inside, secretly, they want to have a lifestyle like here. Let's just be honest. And I think we live in a very, very some people say sensitive, some of my students say we live in a sensitive world, one of my students said this, recently, we live in a much more sensitive world. We live in an interesting time, but I think what is important is that during these changes that we do not lose who we are. We do not lose this thing that people built and created over the last a few hundred years.

00;45;48 - 00;46;06

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Well said. Speaking of cultural translations and bridges, talk to me about Fusion Fest, your involvement, what year you started to participate and how it was grown? It may be helpful to explain what Fusion Fest.

00;46;06 - 00;52;03

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yeah. So Fusion Fest Orlando, I have to say Orlando, so then people are not confused maybe with another fusion fest. It was a nonprofit organization that was founded right here in Central Florida, in Orlando, with the help of Orange County, which we are very grateful for that. And its main goal is to create a space, to shine, to let many, many cultures shine, to create a cultural awareness, to celebrate the diversity of Central Florida. And I joined the organization, back in 2019, first I was there as a sponsor of a Chamber of Commerce booth. And then they invited me to bring some of my cultural, to create a little exhibition, to bring in anything that represent my culture and talk about it. And then someone within that organization and specifically Miss Thali Sugisawa asked me to join the board because she realized that maybe I can bring more, I mean, I was so passionate. I was so excited. I was so excited because that was a place where I not only can talk about my country but also help bring other cultures and country to come and be a part of it. I think that once I joined the board in the first year, we were able to do like a little sort of a delegation from Kazakhstan. We did a little fashion showcase. We did a little, what we call a global exchange, where we have fifteen to twenty minutes to people from different, country or ethnicity within Central Florida to come and talk about them. So whether it is a dance, whether they showcase a video, whether they talk about their culture or share a tradition.

And then I was able to sponsor that same person who was a single mother, was able to get two booths for her, two spaces, so she can sell the souvenirs, and maybe rent out some of these costumes. Not just to showcase the culture, but also to help her maybe get her name out there, to make a name for herself. So that was a very great experience. Now, it is challenging to get all those people together because feathers are ruffled up sometimes, “Oh, I want this, I want that.” It is a toll job. But I think the end goal of this is to create a space. And I always say that the Fusion Fest is like a family. We all like a family. There is no culture to big. There is no culture too small. Everyone is welcome. There is a thing that we say, “all for each other.” We all really live it. So as a Fusion Fest leader, I always make it my job to participate at every event. So if there is a Irish festival, we go and celebrate. If it is a Puerto Rican parade, which was recently, we all go and march along with our Puerto Rican brothers to celebrate them. If it is a dragon parade, which falls into the Lunar New Year, we go in, participate. If it is an Asian American event that we had recently or a Chamber of Commerce event or if it is a Hispanic Chamber of Commerce or any other culture, or [inaudible] that was I think in collaboration with Orlando Museum of Art and Anna Eskamani was one of the people that was sponsoring that. We go there, I make it my job and all of us try to within Fusion Fest, leaders try to go and participate. I think it teaches us not only is there a way to talk about us, but also it teaches us something about another culture. And we all, if you think about it, if we sit down right here, and have a cup of tea or cup of coffee or break bread together, I am a strong believer that if people just regular people like you and I, no leaders, none of these fancy people. Right? But just us. Sit down and have a cup of tea. Share a meal together. I do not think there will be no wars. There will be none of this animosity. Because I am a firm believer that no matter where you come from it does not matter whether you may come from Japan and then from Germany. At the end of the day, we all want to be loved, cared for, we want someone to listen to us. We want someone to appreciate and respect us, and we want to have a happy, peaceful life. We may not express it in a same manner, right? Some of us are more vocal culturally and the other ones are more laid back, right? But in reality, that is what we want. And it may be a cliché to say, but I think deep down, people, they want to have a peaceful life. They want to have a peace on Earth. They want to have a happy life, enjoy it. They do not want to fight with anyone.

00;52;04 - 00;52;33

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Absolutely. Speaking of what this has taught you, what have you learned about Florida through these three major occupations or things that you have done, from your real estate business, from your translation services to your involvement with Fusion Fest, what have you learned about Florida in each of those iterations?

00;52;33 - 00;54;29

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: I think that the Florida, and when I say Florida, I have to be specific. This is mostly Central Florida, South Florida. Because if you go a little bit more north, like Tallahassee, that was a little bit like South, culturally, because it is kind of like a part of Georgia culturally. But I think for the most part, Floridians are very brave people. Because nobody can surpass and overcome a number of hurricanes we go through every season. So I think we are very brave, very resilient, very hospitable. I think the beauty of Floridians is that we are melting pot of cultures, and I do not have to go far. My own family, my husband is from Peru, which is in South America, and I am from Kazakhstan, which is completely different parts of the world. Right. And I think that is the beauty of it. And we make it work. We celebrate each other's cultures, celebrate each other's differences. And what makes us similar. I think that as long as we keep it that way, as long as we keep it that way, I think that Florida, I hope, it stays that way, twenty, thirty, forty years and maybe a century later as long as the hurricane does not come and kill us and knock on wood. Right. As long as the water does not rise and all that global warming thing that is scaring us. But I think it is something beautiful. I think we have that little bit of that island vibe. Not totally, but somewhat and I think that is working for us.

00;54;29 - 00;54;47

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Similarly, you have been here for two decades now, and you have been deeply involved in not just culturally, but also entrepreneurially, how has Orlando, through those lens, changed since 2005?

00;54;47 - 00;56;17

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: It has grown tremendously. I mean, you can see the amount of new communities arrive in and with new communities we talk about our businesses. I think it has grown tremendously. We had over 35% population growth in the last ten years alone. But I think also what beautiful thing that came out of that is if you drive around, if you ever go to Publix, any Publix, and if you have seen, what I have noticed, without even [going] anywhere else, you just go to Publix. And if you go, the amount of that international food aisle how much bigger it became from a little corner, when I was twenty years ago. I think that makes me very happy because we make better each other by learning from each other. I think we make it better. It makes us stronger. It makes us appealing to businesses around the world to invest into Florida. And when businesses come and invest and they feel it a safe place, it gives opportunities to create new jobs. It brings the revenue of taxes to our local government and state. I think it is good for everyone.

00;56;17 - 00;56;21

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What challenges does Orlando face today?

00;56;21 - 00;57;38

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: What challenges? In my opinion, is that, maybe overpopulation, maybe the traffic. I think we are big enough to have some kind of a public transport. And I know we have a SunRail. I think that is a challenging. I think lately, with the whole in, and I do not like to talk politics, but I think one concern for me is whether this whole situation divides people politically. And sometimes I see people of the same families, vehemently defending without realizing that they are the family members. I think it is important for us Floridians to remember that we are Floridians first, that we are family first, right? And then set aside our political views. I think that if we were to do that, I think we will be able to preserve something beautiful that we have here, our peaceful melting pot.

00;57;38 - 00;57;43

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: From your perspective, how will Orlando change in the next twenty years since you have been here for twenty?

00;57;43 - 00;59;32

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: So next twenty years? I think that it will continue to grow that without a doubt. I do not have a crystal ball, but I think it, I wish I did, we will all be millionaires, but what I am thinking is, I do not think it will this beautiful melting pot is going anywhere. That is not going to go. You just cannot make us go. I think it will stay. And I hope there will be more interesting people, diverse people coming, and they will be opening their beautiful cultural centers, restaurants and the Fusion Fest to be there to celebrate all of those people. And I think that, I hope, people will be wise enough to rise above all the, everything and all the noise. Let's just call it all the noise, and they will remember that first and foremost that we are human race we are people and to remember to be humanly kind to each other. And I hope the kindness will not be mistaken for weakness because it feels lately that kindness become a weakness. I think it is extremely hard to be kind to someone, especially when they are being very unkind to you. I think, because in the essence, that was what they used to teach us. Yeah, hopefully that stays. And hopefully it will still be beautiful. It will still be beautiful. And hopefully they will have a better public transportation.

00;59;33 - 00;59;45

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: How has your Kazakhstan heritage influenced your perspective on life generally and living in Central Florida specifically?

00;59;45 - 01;06;18

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: I always say that it is kind of like a play of words. I say that “I live in Central Florida, and I come from Central Asia, so I am always at the epicenter of things.” It was like the words, central. Right. And I hope more people get to know about my country. And it is going so because in the beginning, that was not so because when I would say Kazakhstan, people would say Pakistan or something else. And I think that has grown, thanks to partly that growing, diverse, growing diaspora here. What helped me all those years is that I grew up with, and I saw how some of the challenges my parents faced and the opportunities that we did not have then, and that made me realize how much easier it was to achieve certain things here. And that we had the rule of law and things in place that are there to help people. And there is not anyone—if you are working hard and you are doing the right thing, then there is an opportunity for you. There is not anyone to where someone else is going to come and take a job because they are related to someone you know. But if you are here and you are doing your job, you will be promoted, you will get your break, you will achieve if you work hard. And it does not matter where you come from, does not matter how you look, it does not matter what religion you worship. I think that was it important to me because that was the way my parents raised me.

I think that was one thing that separates me, maybe, or the fact that I am from Kazakhstan versus if I was from, let's say, a more secluded Asian country, let's say, I was coming from China, Japan, somewhere, small town. What is different for me is that I grew up in a very diverse community. I grew up with people of Ukrainian, Polish, Russian, I think Iranian. We had a family with an Iranian background. It was very diverse. German. I still have friends who immigrated to Germany, but they were ethnic Germans, but they were born and raised in my country, that we shared food so we would make stuffed cabbage, and they would make our traditional meal. And funny enough, they leave here, and they make our food. And they call themselves Kazakhstani, ten, fifteen years later since they immigrated. So I think that I almost call it like an utopia that I grew up in this place which prepared me for a life here. So I do not think when I came here, it was not a shock for me to see people of different culture with blue eyes or green eyes. That was not a thing for me. And I think that, maybe growing up there in a diverse community, I felt right at home here. I felt right at home here. I felt right at home with Fusion Fest.

And also maybe work ethic. The way that my parents raised me, the work ethic, the responsibility of giving someone reward, those values that I think that are pivotal to anyone. I mean, those values that can translate that, that are true to any person no matter where they come from. And also, not to be afraid. My grandma used to say that “the fear steals dreams,” if you were afraid of something, you got to do it. You would rather do it and regret rather than not doing it and regret. So I think that what do I have to lose? I came here was $500 to my name twenty years ago. What did I have to lose? It is hell of a scary now that I look back and would I do that journey again? I do not know. No regrets. No regrets because it changed who I am. I think if I was still in my country, I would probably be a little bit more privileged, a little bit more close-minded. I think being able to be here, it gave me a different perspective. It allowed me to meet the person that sometimes challenges me, because he is like a history nut, he loves everything in history. He always correct me if I am wrong somewhere. But also he pushed me to travel. So we have traveled to about twenty countries around the world with him, and it just opened my world, I think. So I am grateful. I do not know what time do I left on this? Whether I am eventually going to go back and retire home because all of us want to do that, right? We all want to go place closer to our families or spend time with my parent. More time with my parents. I think the only the only thing that is on the back of my hand is, not being able to spend as much time with my parents over the last twenty years, and maybe in the next twenty years, I will be working on that. Maybe traveling more, spending more time, bringing them more.

01;06;18 - 01;06;30

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Lastly, if someone is listening to this recording fifty or a hundred years from now, what do you want them to know about your culture and the state of Florida?

01;06;30 - 01;08;49

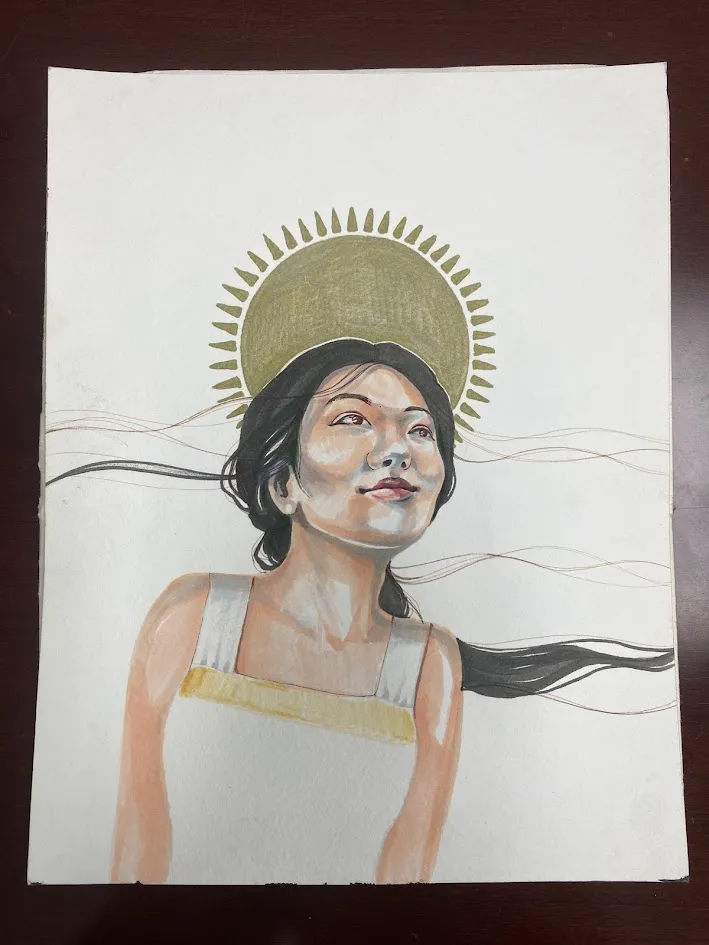

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: So I hope that a hundred years from now, whether it is in Central Florida, which is where I live, whether it is Central Asia, where my country is, Kazakhstan is still going to be a center. It is still going to be important. It is going to be a place of growth, a place of opportunities, a place of freedom. I think a place that celebrates diversity and cultures. And I want to share something which is, something that I did recently, which I did not intend to, but I guess this sort of was kind of in preparation for this without any intention. Somebody asked me to describe my flag and how does it connect to me? So if you look at this, this was drawn probably about fifteen years ago by a friend of mine. She is originally from Uzbekistan. So how did she put this together? She said, so the flag of my country has the sun and then the eagle kind of behind. And then the bright blue sky. So she says that you are heirs as like the feathers of the eagles will forever be connected to your home. So, as I look at the picture, I came up with this is “my roots run deep in the steps of winds of Kazakhstan, where there is always a bright blue sky, a ray of sunshine and the golden eagle watching over the people. And the future. And I wish the same for my country. And I wish the same for state of Florida. Because what type of state it is—a sunshine. So the sun always follows me.” I feel like the sun follows me in the sun. Sun brought me here. And when I first came here to this country, one of my first job, my boss used to call me, “here comes our sunshine.” So may there always be a sunshine whether it is Florida hundred years, two-hundred years, or whether it was my homeland of Kazakhstan.

01;08;49 - 01;08;57

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Kymbat, thank you so much for sharing that and also taking some time out of your day to share your life story. I really appreciate it.

01;08;57 - 01;09;05

KYMBAT IGLIKOVA: Yeah, it was a pleasure. Thank you. Thank you for giving the opportunity. Hopefully it will be interesting for some.