| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Transcription of oral history for Daniel Lam (167.66 KB) | 167.66 KB |

Description:

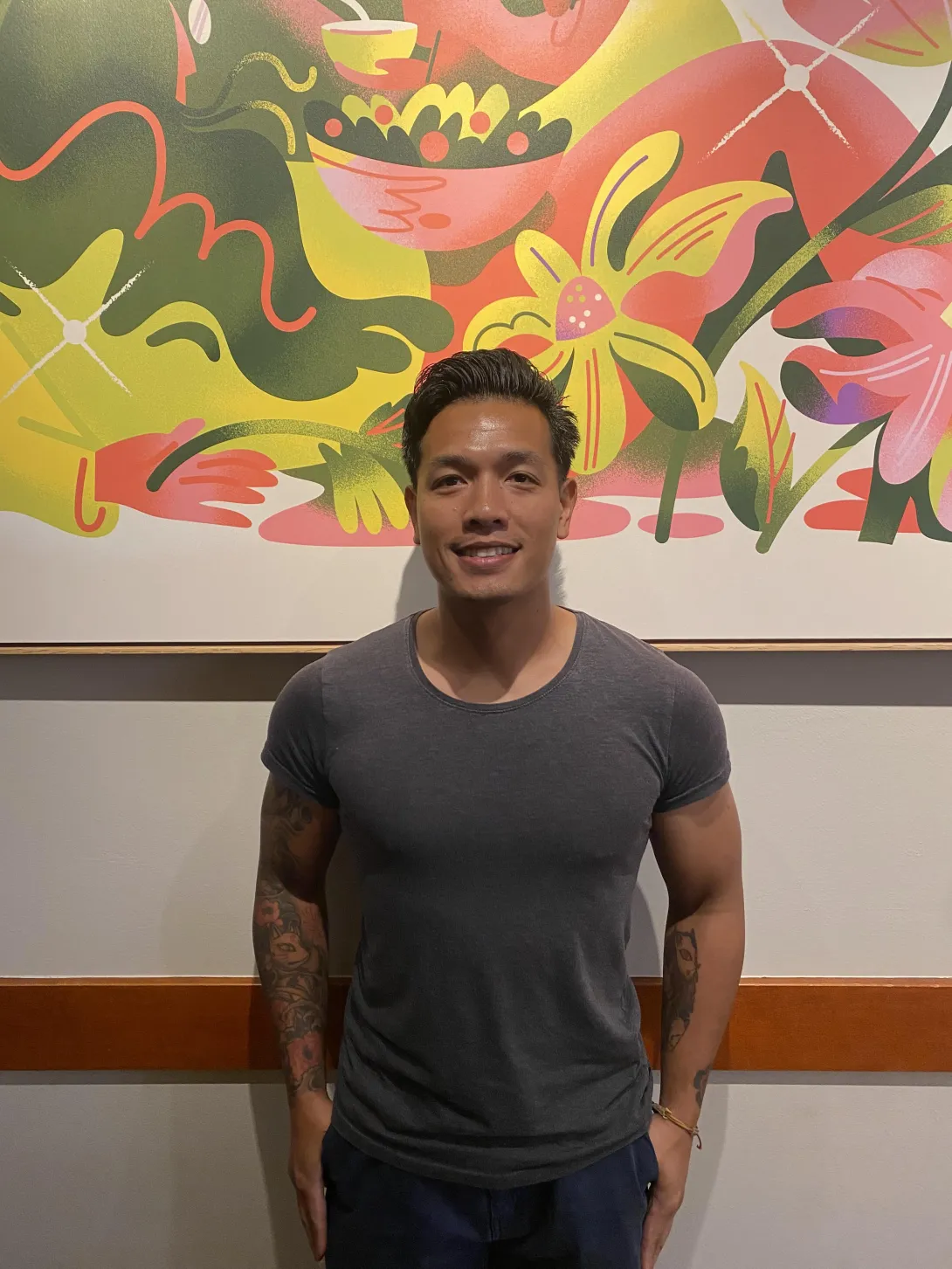

Daniel Lam was born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1990. Daniel recounted his upbringing, particularly the cultural and ethnic challenges he faced growing up as a Cambodian American, as well as stories he learned from his family as refugees from the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot Cambodian killings. Daniel recalled his responsibilities as the eldest child and how they stemmed from Cambodian cultural traditions. Daniel found immense pride as the eldest, setting examples for his younger brothers; however, he also encountered several difficulties by being the first one born in America, such as navigating high school and college, and working as early as fifteen years old to provide financial support for his family. Around 2005, Daniel and his family moved to Palm Coast, Florida, as his parents lost their jobs when Chinese and Mexican corporations acquired and relocated the Texas Instruments factory where they worked. Daniel attended Matanzas High School, further highlighting the racial and ethnic struggles he experienced. Daniel briefly attended Daytona State College, dropping out to work as a full-time sushi chef at a Japanese restaurant to support his family amid his father’s debilitating health conditions. In 2017, Daniel enlisted in the Air Force, serving as a C-17 mechanic. He discussed his military experience and what he learned about himself and American culture during this time. After being medically discharged in 2022, Daniel met his wife, Brittney, following her career in Boston. In Boston, Daniel expanded his culinary experience by tasting foods from various Asian cultures, which later informed his decision to open his own food business. In 2024, Daniel returned to Florida with his wife to remain closer to family. During this time, Daniel and his wife launched their food vending business, Mae Tao & Son’s, as a way to expand Daniel’s culinary passion extending back from his days as a sushi chief, honor Brittney’s father who passed away in 2024, and draw attention to the often overlooked and misappropriated Cambodian and Lao food to the Asian food cultural scene. Daniel discussed early hardships with the developing business and what he seeks to accomplish over the next decade. Lastly, Daniel shared his broader observations about Central Florida, noting that the centrality of food will continue to play a role in maintaining the region’s cultural diversity.

Transcription:

00;00;06 - 00;00;24

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: This is Sebastian Garcia interviewing Daniel Lam on May 27th, 2025, in Panera Bread in Clermont, Florida, for the Florida Historical Society Oral History Project. Can you please restate your name, date of birth and where you were born?

00;00;24 - 00;00;30

DANIEL LAM: Name is Daniel Lam. Born in Providence, Rhode Island.

00;00;30 - 00;00;31

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And when were you born?

00;00;31 - 00;00;35

DANIEL LAM: I was born 05-25-1990.

00;00;35 - 00;00;4

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So before talking about your childhood in Providence, Rhode Island, I would like for you to explain your parents heritage and lineage from Cambodia, correct?

00;00;46 - 00;00;48

DANIEL LAM: Correct. It is in Cambodia.

00;00;48 - 00;00;56

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So, did they ever pass down their experiences or stories, when you were either a child or later in life?

00;00;56 - 00;01;32

DANIEL LAM: Yes, absolutely. So my parents are refugees from the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot. A lot of people know it as the Cambodian killing fields. When my parents came to America, they were not married at the time. They were separated in different areas when they first got here. My father at the time was coming to America through the missionary to Pennsylvania. And the same with my mother. And she came to Oklahoma.

00;01;33 - 00;01;38

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And what were some of the other circumstances that prompted them to leave Cambodia?

00;01;38 - 00;01;54

DANIEL LAM: Oh, the circumstances were through the war itself, during the 1974, around that timeframe, a civil war that raged on for several years.

00;01;54 - 00;02;04

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And can just talk to me a little bit more about the war itself to provide more context.

00;02;04 - 00;02;49

DANIEL LAM: Absolutely. The war itself with the Khmer Rouge, was a regime that tried to overtake Cambodia. And they almost succeeded. Over millions of unreasonable deaths have happened during that timeframe. Mainly the educated, and those who worked for the government were selected off and killed, villagers as well. Anyone with money and they really wanted to break down the people of Cambodia to nothingness, to a blank slate to be overtaken and reimaged.

00;02;49 - 00;02;53

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: When your parents arrived to the US, what did they do for a living?

00;02;53 - 00;04;00

DANIEL LAM: When my mother first came to America, she was still young in her teens. She was probably close to twelve when she first came to America. And the labor laws were a bit different back then. So she got into high school, and it was not the best time for her because, during that timeframe to come to America, you needed a person to be able to speak English, and my mother was the only one who was able to learn English quickly enough. And her coming overseas with her sisters and her brother and her parents, still very young. High school and middle school. Well, high school that for sure at the time was not swell for her. And she picked up a job at a fish factory, cutting fish. And the wage was very low, obviously, at that time frame, in 1980s, and that was pretty much it.

00;04;00 - 00;04;01

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Were you an only child?

00;04;01 - 00;04;06

DANIEL LAM: No. I am the eldest. I have four younger brothers.

00;04;06 - 00;04;10

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Wow. What was it like growing up with being the oldest in a house full of boys?

00;04;10 - 00;04;56

DANIEL LAM: Being the oldest was, I would say different. Some people saw me as the black sheep of the family because I was the first child to go through everything. You know, to learn, to be the best, to make your family proud, to bring honor to your family, to feel all these accolades, to make sure that you have brought family value. And that is the culture aspect with my family, of bringing family value and to bring honor to your family and especially being a son.

00;04;56 - 00;05;03

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What other cultural traditions, habits did your parents instill in you at this at this early age?

00;05;03 - 00;08;43

DANIEL LAM: In my culture, being Cambodian, the first son is to be taken as, like, the second father. So all my brothers had look up to me in that aspect. And my parents have given me that kind of authority in their mindset. If anything was to happen to my father it was up to the first son to take care of everyone else. And I always grew up with that feeling as a child because all my brothers are growing up and they would say, “Hey, listen to your brother. You need to listen to your brother. Daniel, you make sure you do good. So this way, your brothers can follow what you do. You have to be on top of your on top of what you do. You have to be respectful. You have to be known to be the best in certain aspects. And you had to figure it out to do what you need to do.” The hard part about growing up in America, for me, was that, considering that my parents came here as refugees in America, they knew they wanted greatness out of me. They wanted me to be great coming into America. But they did not know how. And that was very hard in that borderline where, it was kind of like you are playing a video game and if you wanted to become a warrior or a monk and all these other skill classes, but you do not know how to take those quests to become that, you know? So my parents wanted me to be great, or to be a doctor or to be anywhere in a medical field or a teacher or anything. But they did not know the objective. What are the path that he has to take the next step? And that was very difficult when your parents are not as educated as you want them to be when they are in America. My parents both grew, and went through high school and got their diploma, and they also became citizens as well. But no one has ever actually went through college or finished college. And that was the difficult part when myself and my brothers went through high school and we had to figure out own guidelines and me, myself going through college and helping my brothers guiding them how to go to college. Myself, I dropped out of college. College dropout, becoming a chef. I was a chef for several years of my time as a sushi chef. And then later on the line, I decided to join the military in the Air Force, which changed my life drastically. It did not just give me structure. I felt like I have always had the structure because being a chef, you have to have structure. Being Asian, myself, being Cambodian, I felt like I already had that structure because I had to be responsible of my brothers. But I had felt the dignity of representing my country, the country that I was born in, the country that had helped my family come to America, to bring honor to my family. That was one reason why I joined in the Armed Forces. In the Air Force, I was a C-17 mechanic, stationed in South Carolina Joint Base Charleston.

00;08;41 - 00;08;55

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And I will ask more questions about your military service. But now, I mean, that was a great analogy. I understood it. They wanted to play the game, but they did not necessarily know the rules how to play.

00;08;55 - 00;08;56

DANIEL LAM: Correct.

00;08;56 - 00;09;23

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And so, yes. And I think that a lot of children of immigrants, especially first gen here, go through a similar experience. But talk to me about some other ways in which you growing up, especially like in high school, maybe even college, you felt different, whether in a positive or negative way?

00;09;23 - 00;12;17

DANIEL LAM: In Providence, Rhode Island? Yes and no. I would say that I got called Chino a lot. Definitely. It is the term for Chinese and in Spanish. I grew up in a very multicultural community at the time in Providence, majority of my neighbors were either Black American or Hispanic American. So I was the only Cambodian at the time in my neighborhood. So they did not know really what was Cambodian. I had a neighbor who was Laotian. They were really cool. But we still were different. You know, we were just neighbors. It was funny because we are neighboring countries, but now we are neighbors next to each other. So that was one of the funny aspects of it. And I ended up marrying a Lao wife that is the irony of my life right now. But, for the most part, growing up, it was different. I did not feel to isolated from my community, as a child in that area growing up, because even though we were different skin tones, and we spoke different languages, we grew up as kids to unify because we were just kids having fun. We did not really call each other like bad names or anything like that growing up. There are some rough patches in the neighborhood in the 90s, of course. And this is when you had a lot of gang violence growing up. The Crips, the Bloods, MS13, all that was very high level in the 90s growing up in that time frame. So I tried to disassociate myself with a lot of the gangs at the time frame during my youth, and that was one of the reasons why my parents had sold their home, to pull me out of Providence and move to Florida because a lot of the association with the gang violence that they felt like if I stayed any longer, I would not have a future. So that was one part reason why we moved to Florida. And the other part was my parents both lost their jobs, due to the factory being moved and assimilated to another country. So one part was China. And then the other part was Mexico. This company my parents worked for was Texas Instruments. If I remember correctly, it was during the timeframe of Bill Clinton and George Bush.

00;12;17 - 00;12;21

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So somewhere between like ’99-2001 range?

00;12;21 - 00;12;23

DANIEL LAM: So it was around 2005.

00;12;23 - 00;12;25

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So later on. Okay.

00;12;25 - 00;14;03

DANIEL LAM: Yeah a little later on, if I remember correctly. Yeah, it was a little later on because I still remember as a kid, 9/11 had happened and I am in middle school, and we were watching it on TV because everyone had brought their televisions out and we were just watching. And I was my last year [in] middle school. I could remember it, the Twin Towers hitting. And we are all watching on TV, just as it happens, right in middle school because my everyone was going crazy about it, and it was a big deal at a time frame. That was one of the biggest deals that happened. My cousin who had served in the Armed Forces, in the Army, we call him tòch, which means small because that was his nickname. We do not really always say our names. You would say nicknames and, he was, at a time when that happened, they were pretty much deploying everybody out for tours. He is alive now. You know, retired, became an officer…. Let me rephrase that. He was in the Army, enlisted, [became] an officer in the Air Force, retired from the Air Force, joined the police force as an officer in Bristol, Rhode Island, and retired as a police officer as well. Big shout out to him. He pretty much help me guide my way through the military. He was a big help for me, and I appreciate it.

00;14;03 - 00;14;12

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So in 2005, your family moved from Rhode Island to Florida? What high school did you attend in Florida?

00;14;12 - 00;16;06

DANIEL LAM: I attended Matanzas High School in Palm Coast, Florida. My time in high school is a bit rough, due to the fact that being Cambodian, there was a massive transition for a lot of Cambodian communities from Rhode Island, that did come to Palm Coast, but they were not as welcome as they wish they was, due to the fact that they did not know what Cambodians were or what or where was Cambodia. And for me, everyone who looked at me thought I was Chinese. So the first instinct for them was like, “Oh, this Chinese kid here.” And I was like, “I am not Chinese.” This nickname kind of stuck with me through high school for a little bit because we were like saying like, “Oh, his name is Dan. Yeah, Dan, Dan the Chinaman.” I am like, “Dude, I am not Chinese, definitely not Chinese.” But you know, I am just going to move on with my day because, I need to focus on my education. My parents moved here for a reason. I got into a couple fights and scuffles due to my ethnicity, and that has happened. If we are being honest and frank things happen, you learn from them, and you just try to get better. I do not have that hate in my heart for whom have done cause to my family, myself, because if I harbor those feelings, I am never going to get anything in life. Things may happen for a reason, so you have to push on, persevere. Just as my parents [did when they came] to America. The agenda of my life and my story would not be dictated by that one negative influence in my life.

00;16;06 - 00;16;13

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Absolutely. And talk to me about, sort of, after high school—when did you graduate high school?

00;16;13 - 00;17;36

DANIEL LAM: I graduated high school [at twenty years old]. This is embarrassing because I graduated at a high school at a year that was not average. When we first moved from Rhode Island to Florida, a lot of my credits from high school did not carry over, so they held me back a year. And then towards, like, my final year of high school, the twelfth grade, I was an unable to graduate due to an English course that I had failed. So they had to hold me back just for one course. And I graduated at an odd year. I have not really told much people about that because I saw it as embarrassing, but it was like really nothing to be spoken of because, who cares where you graduate high school from? So not people really have known that part about me. I think that was the first time my wife actually heard about that part. Wait, did I ever tell you that? Yeah. So I graduated high school when I was twenty. I was basically a part time student. I just come into class for that one class, and they would just let me go and then I would go to work. So I felt like I was already in college. I would work a full time job while I was finishing up that one class.

00;17;36 - 00;17;39

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And this full time job was the chef?

00;17;39 - 00;17;54

DANIEL LAM: I worked at a Japanese restaurant as a sushi chef at the time. Correct. And then I was pursuing college at the same time. So it was it was kind of like a weird moment where you got three things all at once. Yeah.

00;17;54 - 00;17;57

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What college were you attending at that time?

00;17;57 - 00;18;09

DANIEL LAM: At the time, Daytona State College. I was trying to work my way and get some credits, even if I could work at it a little bit.

00;18;09 - 00;18;16

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What were some of the reasons why you worked as a sushi chef?

00;18;16 - 00;20;29

DANIEL LAM: At the time frame, my father was ill. He had suffered from a stroke, heart attack, and he could not work the factory anymore. It was due to him having loads of stress, just trying to cover the bills, realistically, the pay wages were different, significantly different from Rhode Island to Florida. So I had to help my father and my mother pay bills growing up as a child. I got my first job at McDonald's actually, when I was fifteen, sixteen years old, worked basically full time while I went to high school. Taking care of my younger brothers, helping my parents out with the bills, I had to grow up fast. That is something that I just took with a grain of salt because I had four younger brothers, and they looked up to me, and I needed to do what I needed to do. That was my duties as a brother, as the oldest, the family will always have to come first. Bringing that value in for my family. I was just worried that everybody was taken care of, that was what was important to me at the time. Education. I never really thought I would make it to college. I never really think about, like, if I would ever have a chance to graduate high school because, I know it was really important, but I just wanted to get it done and get it out of the way so I can continue working. My mom and my father really want me to go to college, so I went to college, while I was still working. So I worked as a full time student, and I worked at Japanese restaurant full time as well. Dishwasher, cook, chef, you name it. I just filled in all the position because it was job security.

00;20;29 - 00;20;33

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And what was your major throughout college?

00;20;33 - 00;21;17

DANIEL LAM: My major throughout college jumped around a lot, due to the fact that I did not know what I wanted to do. My parents wanted me to pursue the medical field. So I went through the trials and phases for pharmacology. And I went through the foundational stages for the first year, and I dropped out because I just did not like it. My mom and my dad was upset with me, obviously, because I took out loans and I took out grants. But I left it to become a full time chef. My parents were not proud of me at the time frame, because being a chef, they did not really see it as something great or making a lot of money. But it was something that I love to do.

00;21;17 - 00;21;26

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: So your parents were at once upset because you did not pursue the medical route—

00;21;26 - 00;21;27

DANIEL LAM: Yeah Absolutely.

00;21;27 - 00;21;3

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: —but they also understood, like going back to this responsibility that you had as a first child to provide support. So they also understood it as well.

00;21;35 - 00;21;47

DANIEL LAM: They could understand as well because, they start to realize that, oh, Dan, as a sushi chef makes pretty good money.” You know, it held on pretty well.

00;21;47 - 00;21;49

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: How long did you work as a chef?

00;21;49 - 00;21;57

DANIEL LAM: I worked as a chef up until I turned twenty-eight. And that was when I joined the military. I joined it late around, twenty-seven, twenty-eight.

00;21;57 - 00;22;03;01

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And this was all in Palm Coast?

00;22;03 - 00;22;13

DANIEL LAM: Jacksonville. So I had left Palm Coast to Jacksonville later.

00;22;13 - 00;22;2

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: I know you mentioned it before, but so I could ask explicitly, what were some of the circumstances and inspirations that led you to enlist in the military?

00;22;24 - 00;22;40

DANIEL LAM: A lot of reasons. Bringing honor in my family was one, a new turnabout in life, and just being able to provide for my family.

00;22;40 - 00;22;47

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Was the Air Force always the branch you wanted, or was that something that just was brought to you?

00;22;47 - 00;23;56

DANIEL LAM: That was a tough one. I thought about the Army, and I thought about Air Force, and that was something that I always thought about even after I got to high school, because I was like “if I joined the military, I can have structure, it was all the discipline I need. I love martial arts. I love the fact that I am picking a career off the bat, and it just kind of gives me that feel range where I can be at.” For me, I always thought to myself that if I had joined the military at early age, I always thought about it. I think about it now, then maybe my life would have been different, but being who I am now, I do not regret it. All my choices throughout my life, I do not regret anything because it was just these memories and these pieces and experience that create who I am now today, even with all the injuries that I sustained in the military, and all the surgeries, I do not regret a damn thing.

00;23;57 - 00;24;00

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Talk to me about your basic training, boot camp experience.

00;24;00 - 00;25;12

DANIEL LAM: It was cold. I joined during the cold season. So we ran in the cold a lot. Everyone was scared of being yelled at. I just feel like if you just did what you are told, you would not have a problem. So luckily, my group, they were very competitive. Everybody in my group was very, very competitive. You know, we got stuck with, basically a special forces group. So our quarters were right next to them, and we were very competitive with them, like running, pushups, all that. We just wanted to be better than them. And all the guys in my group, they were all mechanics, just like myself. And like, we were just asking around, “what school you are going to after this? You know what did you pick?” I was like, “Oh, I am C—like open mechanic. Never go open mechanic. That was one lesson I learned to myself. Because they can shove you anywhere you like. But that was what happened to me.

00;25;12 - 00;25;21

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: And broadly what was it like for you serving in the military as a Cambodian American?

00;25;21 - 00;27;58

DANIEL LAM: It was definitely different. And come to realize that there are not a lot of Cambodians that are in the Air Force. Majority of the time when I was in the Air Force, I noticed that it felt like the Asian community that had joined the Air Force happened to be either Vietnamese or Japanese or Chinese. And I felt like it was more of like, “Hey, if you are intelligent enough, you can be in the Air Force” type of thing. And a lot of the Cambodians that I have met that were in Armed Forces were either Army or Marine, and it was more like, “Hey, your ASVAB [Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery] scores were not that great. I guess you are going to have to be this job frame here,” which I felt like, I guess maybe could have been a masculinity thing where, a lot of the Cambodians just wanted to be like, “Hurrah! I am going to go. I am going to go do my thing and fight the good fight.” And for me, it was more like I wanted to test the boundaries of my intelligence. I actually scored well enough to go into the intelligence field, but I was in a rush to join, because if I had waited, would it take a year for my recruiter. I felt like he possibly kind of bluffed me out to be honest. And, I was like, “Okay, I guess I cannot get that job that I wanted.” So I went open mechanic to get shipped out as soon as possible. Unfortunately, at the time when I was joining and did my ASVAB score, I got it in, I scored over seventy-five, seventy-seven, somewhere above average. And the head sushi chef that I worked with at the time, was like, “Hey, I heard you join the military. That was what you want to do? [I replied] “It was just something I am thinking about. You know, I have not signed anything just yet.” And he was like, “Well, you are done. Pack your bags, get all your knives. You are not working here anymore.” So he fired me on the spot when I told him what happened. And in my head is like, “I do not think he can fire me. But you know what? If he does want me here, then I can leave.” And I told my recruiter, [and he said] “he is not supposed to fire you. That is actually against the law. They are supposed to keep you until you ship.” And I was like, “Yeah, they fired me. When is the closest ship date?” “Well, we can get you out here next month.” I was like, “All right, fine, let's go.” So I went open mechanic. That was one of my reasons because I just did not want to be out of a job.

00;27;58 - 00;28;05

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Yeah, absolutely. Wow. Thanks for sharing that. So how long did you serve?

00;28;05 - 00;28;55

DANIEL LAM: In total, my contract was for six years. I got injured one year prior before my actual service date was supposed to be done. I had fracture lines, and I had broken bones and a torn Achilles at the time frame of my injury. I basically had a reconstructive foot surgery, and it impaired my walking and running. I still try to work after that, and it just did not work out, due to the fact I could not really apply myself to run anymore for my fitness tests. And I was medically discharged, honorably.

00;28;55 - 00;29;10

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Yeah. Absolutely. So six year contract and you joined in 2017, correct? So 2021 was when you finished your service.

00;29;12 - 00;29;15

DANIEL LAM: 2022.

00;29;15 - 00;29;23

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What did you learn about yourself and the United States serving?

00;29;23 - 00;31;17

DANIEL LAM: I did not know it, but I guess I am really good at leading. I know how to take control and know how to speak to people. I love the idea of having everybody work together and just being able to be involved because it just makes everything streamline. I learned that I was able to empathize with a lot of people, people of different backgrounds. And just really just try to help people. My goal was really just wanting to help people, you know? How can I help? That was what I wanted to do. I took in that part of my self, service before for self. And I still kind of take that a part of me when it comes down into the culinary world where it is service before self, and I need to tone that down a little bit because my mom is telling me that I need to take care of myself a bit more. And what I learned from the military is that structure is a good thing. And it welcomes diversity. Being in the Air Force, welcomes diversity—I cannot think of any possible place where you can meet somebody from Kansas and then have somebody from New York and then have someone from Hawaii, and then have somebody from Alaska meet in one spot who have no ties together and still get to know and understand each other.

00;31;17 - 00;31;17

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Well said. Absolutely—

00;31;17 - 00;31;40

DANIEL LAM: Because we are united for one reason, and I made plenty of friends from different parts of the world and it is a beautiful experience. I will say for that you are going to have to face a lot of hardships together. But hardships make and break you and majority time, it will make you, if you allow it.

00;31;41 - 00;31;50

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Absolutely. So, from 2022 onwards, what was sort of your life trajectory at that point?

00;31;50 - 00;39;35

DANIEL LAM: That part was hard. So, I found out that I was losing my job. I became depressed, you could say. I did not know what I had left because I put it all of my efforts, everything, eggs in one basket, I went to college for trying to become an officer, I had moved all the way to a state that I am not familiar with and I am okay with, and here I am trying to learn how to walk again because I am stuck in a AFO [Ankle Foot Orthosis], which is the ankle foot brace, possibly for the rest of my life. And my mental state of mind was that I do not know what to do with myself anymore. And a lot of my friends that I was close with, that time frame had PCS [Permanent Change of Station], which is another term [for] going to another station. They being station somewhere else. They move me somewhere else. They going to Hawaii. They have going out of the state. And it was just me. I am living on my own, and I am trying to figure out what I need to do next. So, I just kind of worked until I was finishing up my contract, and I suddenly met Brittney [his wife].

And I met Brittney near towards the end of my contract, and we just talked as friends and such, and I did not know if she was actually going to come visit me. She actually came to visit me, and we started to go on dates. And we later on, built a relationship, becoming boyfriend and girlfriend. And she moved down like the last three months of my contract being set up. And then, she had picked up a job offer in Boston, and I was like, “I guess we are going to Boston, you know?” So we went to going to Boston together, and I started going to college in Boston at UMass Boston, for Computer Sciences, trying to figure out what I needed to do next. It was not necessarily something that I love to do, but it gave me some time to just reinvent myself, trying to figure out a new career that I needed to figure out. And we became really big foodies in Boston, so we just had to try everything out. We had [gone] to Chinatown. We had [gone] to these omakase, which is a Japanese course meal, which is close to fine dining in an aspect of it. And Japanese kaiseki, which is another form of course meal as well. And it really opened my mind and perspective on my palate of just trying different foods. So Japanese food, Chinese food, Southeast Asian food, Jamaican, Filipino. All these multicultural things that was going on in Boston and it enlightened my culinary fuel to figure out what I wanted to do next. And suddenly I got a call from my mom and my dad, and they were like, “Hey, Dan, you want to come visit us in Palm Coast?” And we would make trips back and forth, driving to the Palm Coast here and there for a couple of years. And one day I was talking to Brittany, and, I said, “Have you ever thought about moving to Florida? Just giving it a chance and we would be close to my parents” because I have not seen them in so long after my service. And I was just like being closer to family. And I really wanted that. And that was also at the time frame, we recently found out her dad was diagnosed with cancer. So we were just trying to figure out what can we do? We did not want to make too much of a drastic change. And just last year, sometime in August and September, we moved to Florida.

I am still in college, and I was wondering to myself, “I still love to cook, and I really want to do it again, but I do not.” And I was telling Brittany's like, “Well, I got some free time. I could just be a chef.” And she just talked to me saying, “Why don’t you just be a chef for yourself?” That would [required] me to have my own business like, “I do not want to be a chef, I guess, unless I owned it myself.” And she said, “You can do that.” And I was like, “Start my own business?” “We would do it together.” And so we thought of the idea of doing a pop up and that was part of “Mae Tao & Son’s” started. The other part was that we wanted to pay homage and honor her father who had passed away from cancer. And it really trigger an event in our heads saying that culture is very important. Food itself is culture. So without food, there is no culture. Because food is provided to you every day of your life. Breakfast, lunch, dinner. All this is culture. And if you consume it three or four days, seven days a week. 365 days of the year. You are a part of that culture, and that culture has to speak to you. If you do not practice the food of the culinary of that culture, you lose that aspect. So in my mind is that I am first generation and I want to be more involved in my culture, and she wants to be more acquainted and showing the respect that the culture deserves and same thing with myself for the Cambodian culture [through] food, and be able to pass that down to the next generation, whether it is our children, the children's children, either we have to be the pioneers for that—and it is okay—but if we do not then culture could die out. It is preserving the culture that is really inspiring us and what we will like to do and is a very hard journey because Cambodian food and Lao food is not really known, it is not really recognized. And that is the hard part about being a chef for Cambodian and Lao food, even though it is delicious, it is hard because it is not as marketed.

00;39;35 - 00;39;49

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Absolutely. And talk to me about what these first couple months starting the business officially in 2025, the growing pains you have had to experience and what you have learned?

00;39;49 - 00;41;32

DANIEL LAM: Ooh, that is a tough. The growing pains was definitely location, being a pop up. One spot, we were in Pinellas Park in Florida, which is like the little underbelly of Saint Pete, we thought we were going to do great. We thought we were going to nail it. We ended up not doing so well there, and it was one of the hardest parts of the situation to pull out of that location, because we felt like the time and money that we placed in there, it did not really bring us anywhere. So we had to look elsewhere. As we start to learn the places that we were welcome and the food was being taken in, we worked with a lot of bars and breweries to kind of just find availabilities for us to pop up. And we started doing night markets, which was more Vietnamese oriented. And they were a bit oversaturated with other vendors, which made it very difficult for you to operate. One key thing of being part of those night market is that you have to have your niche. You have to sell something that is going viral. Everybody wants to get something that is going viral. For me, I do not want to be that person. I want to be authentic to myself. I do not want to sell it because it sells. I want to produce food, create food, and appreciate the food and have the love for it because if you do not love what you are doing, then what is the purpose of it all? Why try it all? Why do at all?

00;41;32 - 00;41;39

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Where do you see your business a year from now, five years from now, and ten years from now?

00;41;39 - 00;43;35

DANIEL LAM: A year from now, I really hope that I have a food truck by then. That is the goal. This way it makes traveling and service a lot easier from a pop up. Five years from now, I really hope to have a brick and mortar, possibly a cafe, and kind of build it into where it becomes a staple for other people, where they can walk into your local cafe or restaurant and order the food that is a reminder of home. And I want that for people when they have a dish of mine or have a dish from me and my wife, and they eat it and they just think about “man, if I close my eyes and I eat this, it just takes me back to where I grew up with my mother and my father,” and that is where I want people to feel—at home. I want them to have a sense of home. And that is the very important part. Ten years from now, I hope to have a tasting menu where it it is taking food that we all love [and] giving it another plateau in level where it is a contemporary style. Where the food is transformed and still familiar to you but is still representative for Cambodia and it still representative for Lao. You have all these flavors there, but there was so much potential to push out.

00;43;35 - 00;43;45

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: You have been in Florida since 2005, give or take. From your perspective, how has Florida changed culturally?

00;43;45 - 00;44;39

DANIEL LAM: I feel like it has changed drastically. From 2005 until now, I feel like the Asian culture community has grown tremendously. Not so much for the Cambodian community and Lao community, but overall still it is still the Asian community, and it has grown. You know, it has grown tremendously. It is a lot more welcoming, cultures a lot more diverse. People are seeing that there is more than just Chinese, which is very important because you have all these other heritage of Asia, you have Koreans, you have Japanese, you have Cambodia, Burma, Thai, Lao, Vietnamese, Filipino, Polynesians, Hawaiians—they still kind of fall into that aspect.

00;44;39 - 00;44;43

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What challenges does Central Florida face today?

00;44;43 - 00;45;3

DANIEL LAM: I believe that it really faces the food costs of anything, pay wages, food costs. That is one of the biggest things that faces now is with everything going up in prices, even my mother, who walks into the Asian stores and the regular stores, generally, it is hard. It is hard to buy anything. You know, you are second guessing yourself if you really want to buy this to make this at home or not. Is it worth it? Or are you going to have to squeeze every penny as much as you can and see where it can stretch?

00;45;33 - 00;45;39

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: From your perspective, how will Florida change or Central Florida change in the next twenty five years?

00;45;39 - 00;47;04

DANIEL LAM: It is a bit of a surprise. It is what I hope. I cannot predict everything. I feel like the Lao community and the Cambodian community will be more recognize, be more open to speak, be more willing to be prideful of where their heritage came from, in a way, because I feel like being Cambodian American, it is kind of like you are scared to speak out loud and say that this is who I am. If I had to make a quick video of myself, it would definitely be like, “Hi, my name is Dan. I am a chef, and I am Cambodian American.” And I feel like a lot of people are scared to say that, like they are Cambodian American, or they do not want to be open to who they are. And that is the hard part because Asian folks in Florida, they are a little timid and that is what I have noticed. And it is not a super bad thing, but I hope that they will not be as shy twenty five years from now.

00;47;04 - 00;47;07

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: What impact do you hope to make culturally with your business in Florida?

00;47;07 - 00;48;25

DANIEL LAM: I really hope I am able to unify some parts of the Cambodian community and Lao community to really start a wave for the next generation to say, “Well, this guy, he is Cambodian American, and he became a chef, and he did this, and he did that. And there is other people who done all these other things to, like, become a lawyer or become a doctor.” That there is hope for them and there is a chance for them to be something in life. Being first gen, the children of Cambodian folks, they did not have much to look up to. There is no Cambodian idol they can look up to in America. And it is hard to find one because they are not really staring at a Cambodian idol. You know, there is no guideline. And I hope to be a part of that role model where I can be something for them. You know, I hope to, even without me knowing because I just hope to inspire. My goal is to inspire. And that is part of my goal.

00;48;25 - 00;48;38

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: How has your Cambodian heritage influenced your perspective on life generally and living in Florida specifically, or the US?

00;48;39 - 00;50;14

DANIEL LAM: I treat life greatly. Life is short, very short. I learned about how it is so easy to lose somebody. And you really do not take a lot of things for granted. You come to terms of appreciation of what here in America, the values of opportunity has given you. I look at all my choices in my life. I am only thirty five. And these chances and opportunities that I get, and I cannot say that all of it were blessings, but I take certain things as a blessing. Even though certain time frames of my life where I look back and say, “Wow, that went horribly wrong. But maybe it was a blessing in disguise for me to be who I am now and be optimistic and look about it that way, because I still had opportunity and chance compared to some other people that did not have a chance and opportunity in a different country. You know, in Southeast Asia. And I take that highly of myself to say, I had this opportunity and chance more so than others. And I should respect that, and I should acknowledge that as well. And I am grateful for it.”

00;50;14 - 00;50;24

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Lastly, if someone is listening to this recording fifty or a hundred years from now, what do you want them to know about your culture and the state of Florida?

00;50;24 - 00;50;50

DANIEL LAM: I would like to know that the people of Cambodia are warm hearted, loving people. And that in the state of Florida, while the sun may shine and it rains, you still have a chance to do wonderful things in life.

00;50;50 - 00;50;58

SEBASTIAN GARCIA: Daniel, thank you so much for taking some time out of your day driving from Tampa to come met with me and share your life story. I really appreciate it.

00;50;58 - 00;51;01

DANIEL LAM: Absolutely. Hey, thank you. Thank you so much.